As medical providers, we are quite adept at communicating in our normal day to day environment within the hospital and understand the importance of providing concise, detailed, and relevant information to other caregivers. Communication skills are also of particular importance when we are off climbing a remote mountain or on an evening climb session at our home crag. The ability to communicate in the high-risk environment of the climbing world is often as important as the gear used to ascend a pitch.

In my work on the American Alpine Club’s yearly publication, Accidents in North American Climbing (ANAC), I often edit reports of communication breakdowns between climbing parties that result in death, injury, or near misses. Additionally, I have seen numerous instances where communication difficulties between climbers and search and rescue teams has caused delay in care. In this two-part series, we will be discussing both. This first article will emphasize the importance of understanding common climber vernacular by search and rescue teams, and the second column will discuss transitioning from ascending to descending by climbers, as this is a common time for communication breakdown that results in injury.

Communication between climbers and search and rescue teams (SAR)

A common communication problem between climbers and SAR is a “lost in translation” moment that occurs due to a lack of knowledge of climber terminology. Most outdoor user groups have language or slang that has developed within the group to describe techniques, locations, and gear. This terminology is often different than what the search and rescue community uses for the same things. While many SAR team members are also recreational climbers, this is not always the case. By understanding climber terminology, SAR teams can improve communication with injured parties and hasten rescue.

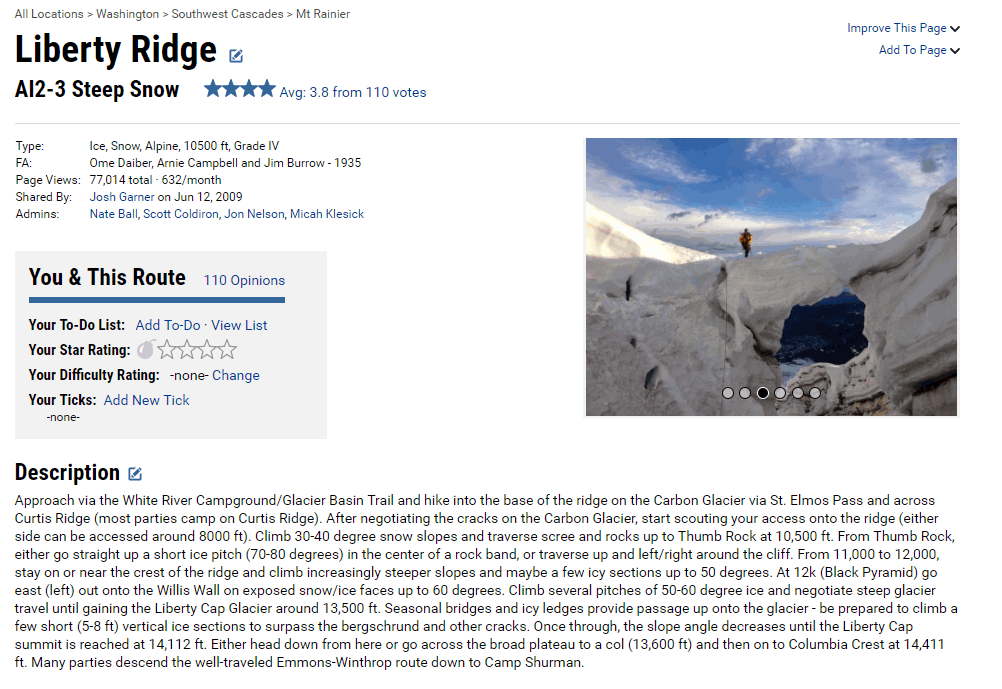

Guidebooks and Apps

The first step in speeding rescue is the acquisition and utilization of climbing guidebooks by search and rescue teams. I often recommend that teams keep a copy of the local climbing and hiking guidebooks in all team vehicles and to provide at least one copy each to the local 911 center/emergency dispatch. Additionally, it is helpful for search and rescue team members to be familiar with the Mountain Project app. This app lists most major climbing areas in the United States. While it is user sourced, not entirely comprehensive, and provides unverified information, I have found it to be useful in identifying climbs in unfamiliar areas. This app and website are available for free on most platforms.

While every climbing area has a host of locals in the region that know and use both climbing names and correct geographical names to describe a location, many climbers are from out of town and may not know proper road names or numbers and would be hard pressed to describe their location using anything other than climber place descriptions found in guidebooks. Additionally, in an emergency situation, these climbers will likely not have the time or ability to flip through their guidebook or search Mountain Project to find these proper place names. Therefore, it falls on the local rescue team to translate an injured climber’s description, often just a route name, into a usable location prior to sending a team to assist. Access to a climbing guidebook is the quick solution.

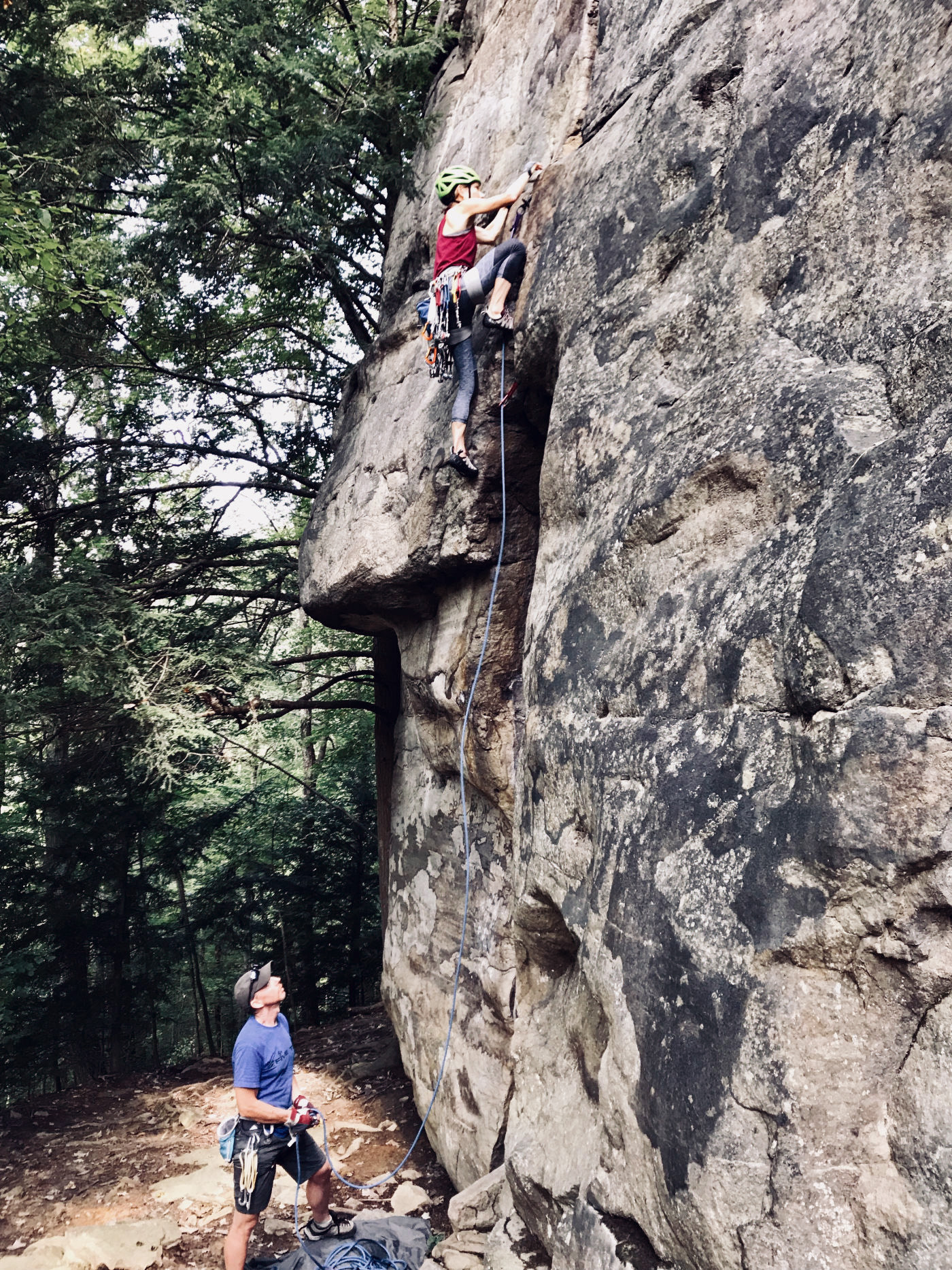

Here is an example from my home crag of the New River Gorge, WV.

“We need help, my climbing partner fell on a climb called Springboard at Orchard Buttress and hit his head. He seemed okay at first and we began to walk out. He got dizzy and had to sit down at the base of the climb called Arbor Day. He is going in and out of consciousness. Please send help.”

To a climber or rescuer unfamiliar with the area and without a guidebook, this would not make much sense. But with the help of a guidebook or a local climber with knowledge of the area, this is actually a pretty good description and could be quickly translated to the following:

“We have an injured climber at the Fern Buttress area of the gorge and need to get a team there ASAP. The climber is now at the Wild Seed area, about a 15-minute walk from the first parking area, one mile down Fayette Station Road (Rt. 82).”

As you can see, by simply referring to a guidebook, rescuers can be better organized and respond more quickly to this accident.

Training

Integrating climber names for locations into training exercises can also greatly increase response times in the case of an actual emergency. I recommend that teams use guidebooks as part of their training exercises. Rather than relying on GPS coordinates and street or road names to guide them to the location of the accident, a good training exercise is to give a team instructions that a climber would use to describe a location. It is also important to mention that many guidebooks provide GPS coordinates for the start point of climbing routes.

Since members of search and rescue are not always local climbers, by acquiring and using local guidebooks in rescue and in training, misunderstandings can be minimized and make for quicker rescue of injured climbers. Additionally, many climbing areas have climber non-profit organizations that can be of assistance to search and rescue teams in planning for and responding to emergencies. These groups are usually comprised of local climbers who are energized to do good things for their local crag and climbing community. Outreach and coordination with these types of groups can also be useful in minimizing communication miscues.

Looking for additional information? A great resource regarding communication between search and rescue teams and user groups in general is Chapter 6, and for climbers in particular, Chapter 25 in the recently released textbook, Wilderness EMS (Wolters Kluwer).