In our first article on safety innovations, we discussed belay devices and techniques. In our second article, we discussed advances in rock protection. These pieces of equipment and techniques saw relatively rapid adoption amongst climbers once introduced. Very few climbers today would seriously consider not using modern belay devices or rock protection. However, many climbers will happily climb without a helmet. In this article we will discuss climbing helmets.

Original climbing helmet, Alpinist.

The Brain Bucket

Climbers did not originally wear what would be recognized today as a climbing helmet. Many difficult first ascents were completed with no significant head protection. As we discussed in the previous articles, a lead fall for early climbers was to be avoided at all costs since the results were typically catastrophic. Thus, the main head injury risk was rock or ice fall. Helmets for other purposes did exist but were too heavy or bulky to be practical for climbing. The change began in the 1960’s when new materials enabled a British climber named Joe Brown to create the first helmet purpose-made for climbing. Made from fiberglass and polystyrene foam the helmet was incredibly heavy by today’s standards but was durable and offered a great degree of impact protection. At the time, it was the most viable option for climbers looking for increased head protection. However, due to the weight and lack of ventilation, many climbers still chose to forego a helmet. The design persisted into the 1990’s when new technology again brought change.

Look good to send good!

Over the last three decades, new materials, testing standards, and designs have allowed climbing helmets to become increasingly light and comfortable while still offering adequate protection. Also, because a helmet only works if you have it on, modern helmets have become significantly more stylish than older models. Helmets today fall roughly into three categories, hard shell helmets, foam shell helmets, and hybrid helmets. Hard shell helmets are made primarily from a single thick layer of molded ABS plastic. These helmets are inexpensive and very durable making them good choices for intense use. The drawback is these helmets are heavier than other options. Foam shell helmets are made from either expanded polystyrene (EPS) or expanded polypropylene (EPP) and are often coated in a thin layer of polycarbonate plastic. The thin coating of plastic increases protection from minor abrasions or impacts. The foam is effectively able to absorb an impact. These helmets are lightweight but are also more expensive and fragile. While a hard-shell helmet may be able to take many significant impacts before needing retirement, a foam helmet must be retired if the foam is deformed from a single impact. Hybrid helmets combine the two technologies. They are primarily made from expanded foam but have a covering of ABS or other hard plastic targeted to areas of the helmet most likely to see an impact. This style of helmet is typically the lightest but also the most expensive and has the same durability concerns as pure foam shell helmets.

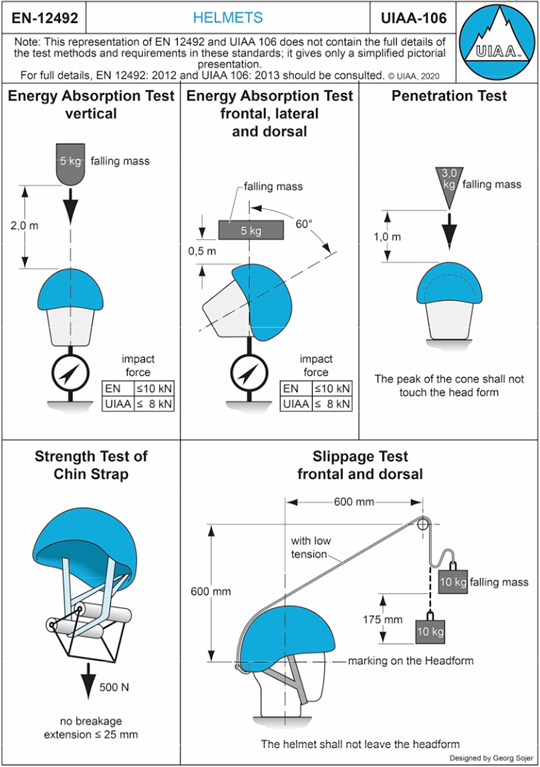

Testing of climbing helmets, UIAA.

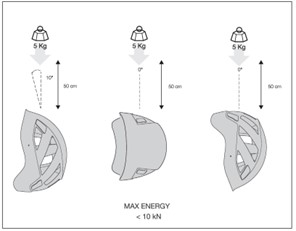

Climbing helmets are tested according to standards set by the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) or the Union Internationale des Associations d’Alpinisme (UIAA), also known as the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation. These organizations set standards for most of the equipment used in climbing. For climbing helmets, the relevant standards are EN-12492 or UIAA-106. The helmets are tested to provide the most protection from a falling object striking the top. The helmet standards allow for significantly less protection from impacts to the front, sides, or rear of the helmet and from object penetration. The chinstrap is tested to ensure protection from breakage and loss of the helmet. Slippage of the helmet is also tested. With the increasing popularity of sport climbing, where the risk of rock fall is lower and the risk of side or front impact from a fall is higher, there is concern that helmets need to provide more side and front protection. The manufacturer Petzl has been advocating for additional protection to these areas and has devised an in-house test for increased standards. Many factors can be considered when choosing a helmet, however the helmet must fit properly and should be certified to either the EN or UIAA standard.

Petzl front, side, and rear impact standard, Petzl.

Where are all the helmets?

Climbers today have a variety of lightweight, rigorously tested, and affordable options for helmets. Despite this, many more climbers choose to climb without a helmet than they would other safety equipment such as a harness or rope. It is well known that head injuries can have fatal or otherwise devastating outcomes. However, several studies that have investigated climbing injuries report a wide, but non-insignificant, incidence of head injuries. One study showing high use of helmets (Rugg et al) was conducted using data from the Austrian Alps which may have a different helmet culture than the US. Their data show statistically significant higher odds of serious or fatal injury among climbers not wearing a helmet. Data from McDonald et al show that head injuries appears to be more common during traditional (trad) climbing. In that sample, 8.7 % of injuries during trad climbing involved the head; compared to sport climbing (4.7 %), bouldering (1.6 %), and indoor climbing (0.4 %). This fits with anecdotal evidence that helmet use is higher among trad climbers and climbers engaged in other activities perceived to be higher risk, such as ice and alpine climbing.

The reasons for lower helmet use in sport climbing appears to be multifactorial. Since sport climbing is seen as lower risk, helmet use is not seen as important. While it is generally true that sport climbing has a lower risk of serious injury or death compared to other types of climbing, injuries can still happen while sport climbing. Injuries can also occur on overhanging routes which are usually considered “safe” for falls. Many photos and videos of the world’s top sport climbers depict them with no helmet which is likely a contributing factor. However, when weighed against the protection offered by modern helmets, there is not a good argument against their use.

Bottom Line

Modern helmets are marvels of lightweight materials and engineering. Helmets cannot totally prevent head injury. However, they do offer protection against severe head injury and can often prevent minor injuries, such as lacerations. Climbers and belayers both should wear appropriate head protection while engaging in all types of climbing.