Twack! The unmistakable pop of my foot hitting the ground from a 15-foot drop jolted me with an immediate sense that something had gone wrong. It was the end of the day, and, having fallen again and again from the same bouldering problem, we’d neglected to check for gaps between the pads. On that unlucky fall, my shoe slipped between a crack in the pads. Many doctors’ visits, X-rays, MRIs, and weeks of crutches later, I swore off bouldering and turned to the ropes, for what I believed to be the safer alternative in climbing.

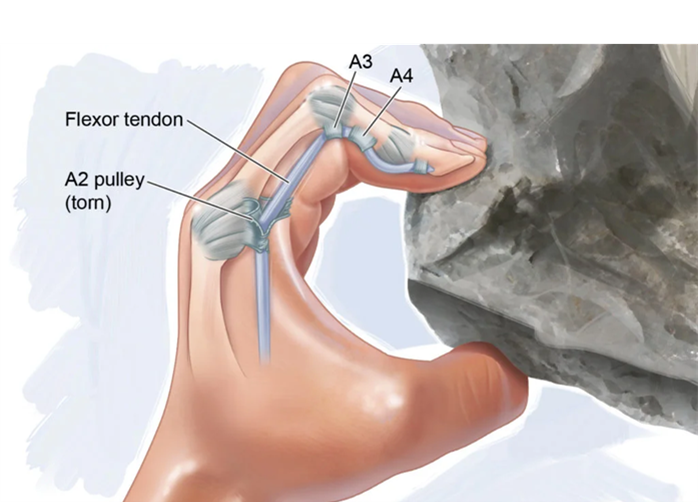

But was rope climbing truly safer? Anecdotal evidence from friends at the gym told me that yes, it was, as it seemed that every other week someone I knew was out of commission from some bouldering injury or another. Whether it be a finger pulley injury (see Fig. 1) from an explosive bouldering move, or an ankle sprain from a bad landing, the strenuous nature of bouldering seemed to lend itself to injury. Climbing with ropes, albeit to greater heights, offered the safety of a rope to catch one’s fall. The longer routes favored endurance over power, lessening the strain on the muscles and tendons. The roped side of the sport seemed to lend itself to longevity, especially when compared to bouldering. A glance at the demographics of each respective discipline in any gym or crag will likely confirm that (ergo, the popular phrases “trad dad” versus “boulder bro”). But what does the data say?

Fig. 1: Finger pulley injury– rupture of a ligament (ie. A2, A3, or A4) that attaches the flexor tendon to the phalange

A search of the literature reinforced my suspicions. A survey of outdoor boulderers in some of North America’s most popular bouldering destinations (Moab, Joe’s Valley, Joshua Tree to name a few) found that an overwhelming majority of boulderers (86%) sustained injuries over the course of a year. This finding was not limited to just outdoor boulderers; the same study found the same frequency of injuries in primarily indoor boulderers as well. Another study surveying climbers from indoor bouldering gyms in Germany found that the majority of climbers (55%) had at some point in their climbing career sustained an injury that had put them out of work or training for 10 days or more. Over the 6-month period of the study, 44% of the 507 climbers surveyed had injured themselves (an event qualified as an injury if it caused the climber to take 1 or more days off work or training). It seemed fair to say that if you were a boulderer, you accepted injury as an inevitable part of life.

In general, there are three different ways one can be injured during bouldering: either while climbing, falling, or spotting. The most common injuries were overuse injuries sustained during climbing to the upper extremities, in particular the fingers (67% of outdoor boulderers in Josephsen’s study over the course of a year). Trauma from falls more often resulted in injuries to the lower extremities, and these were usually more severe[1], requiring some form of medical outpatient therapy. Studies from US and German emergency departments found that for bouldering, the most common injury to present to the ED were those to the ankle, followed by the knee. My own fall had resulted in multiple grade 3 sprains to both the medial and lateral ligaments of the ankle, and a friend’s awkward landing from a bouldering problem in the gym resulted in an ACL and meniscal tear. Both required weeks of crutches, months of outpatient physical therapy, and, in my friend’s case, a long recovery after surgery. While my own experience has certainly contributed to my departure from bouldering, the data has only served to confirm my fears.

Perhaps the notion that roped climbing was safer than bouldering was a naive one, however. Despite the reassurance of a rope, the inherent risks of climbing to greater heights meant there was potential for greater consequences. Indoor gym climbing walls generally range from 40-60 feet, about the height of a 3-4 story building. How likely was one really to sustain a serious injury while roped up?

A prospective analysis of an indoor climbing gym in Germany looked at the incidence of climbing injuries over 5 years. From 515,337 visits to the gym, 32 injury events were recorded, 30 of which involved actual climbers (the remaining 2 were unlucky spectators). An event was only categorized as an “injury” if paramedics or a physician were called to the scene. As it turned out, the majority of climbing injury events reported were either during lead climbing or top-roping (53% and 23%, respectively), with only 6 bouldering incidents qualifying as an injury (20% of the total injuries). Of the 9 incidents that resulted in permanent disability, 7 involved ropes, demonstrating the severity of rope climbing fall potentials. Injuries included bilateral calcaneal and ankle fractures, vertebral fractures, and two cases of polytrauma (multiple fractures, abdominal injuries).

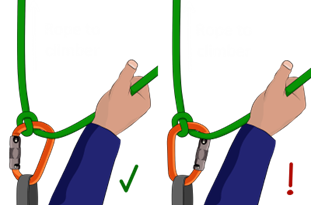

Fig. 2 Basic Top Rope

A third of the incidents were due to belay mistakes[2]. What was surprising from Schoffl et al’s study on indoor climbing injuries was the high incidence of injuries while top roping (23%), usually considered a fairly safe form of climbing. In top-roping, the climber is attached to a rope looped through a set of anchors from above, which is pulled up by the belayer as the climber ascends (see Fig. 2, left). Falling usually results in minimal vertical movement. In contrast, in lead climbing the climber is attached to a rope which follows them below, and they clip the rope into quickdraws attached to the wall on their way up (Fig. 2, right). Fall distances are greater due to the rope often being attached to the wall below the climber.

Fig. 3: ATC

Fig. 5: Munter hitch

In Schoffl et al’s study, all the top rope injury events either involved the use of an ATC or Munter hitch (Fig. 3, Fig. 5, respectively). These belay mechanisms lack an automatic braking system if the belayer lets go of the rope. In contrast, assisted-braking devices, such as a GriGri (Fig. 4), automatically halt the rope from slipping through the belay device when the rope is pulled. Many US gyms now have GriGris automatically installed into their top-rope systems and require use of a GriGri or other assisted braking device while lead climbing, a measure taken to mitigate risk of user-error in belaying.

As scary as the potential for severe injury is, the incident rate for indoor climbing is exceedingly low, with an acute injury risk of 0.01 to 0.03 injuries for every 1000 hours spent climbing at the gym. Another study that surveyed sport climbers estimated an acute injury risk of 0.2 injuries per 1000 hours climbing, both indoor and outdoor. In comparison, American football has an injury risk of 15.7 injuries per 1000 hours of sport performance, motorbiking 22.4, and ski/snowboarding 1.0. Competition climbing did see higher rates at 3.1.

When taking to the outdoors, injury rates increased, as one would expect. An old study done on Yosemite climbers from the 1980s cited the injury rate to be as high as 37.5 injuries per 1000 hours of traditional (or “trad”) climbing, a form of climbing outdoors which requires the climber to place their own pieces of gear (or “protection”) into the wall to protect their fall, rather than clipping into pre-placed bolts. A recent study confirmed that traditional climbers sustained more injuries on average when compared to other forms of climbing, with an average of 2.53 injuries versus a mean of 1.92 of all climbers surveyed.

Fig. 6: A climber (Roger Schali) on the north face of the Eiger

The most beautiful climbing destinations are often in remote regions of the globe, and not readily accessible by vehicles or other means of evacuation. Desolate landscapes and preserved wilderness offer climbers an arena to test not only their climbing capabilities, but their navigational and survival skills, albeit at the risk of more technical and logistically difficult rescues should they be needed. And unfortunately, when accidents do occur in the backcountry, they are often needed.

Climbing accidents make up about 12% of the 306 severe polytrauma cases[3] in the International Alpine Trauma Registry (IATR), a database of multisystem trauma patients encountered in remote or mountainous regions in Europe[4]. Analysis of the data showed the most common mechanisms of injury to be from fall onto the ground, fall into a snowfield, and impact by rock fall. Injuries to the head and neck, followed by those to the chest, were the most common. While the majority of victims survived until hospital discharge (83.8%), only about half had good neurological outcome. Another study on emergency rescues in the Austrian Alps showed that the most common injuries in climbers who sustained falls of 5 meters (16 feet) or greater were fractures and dislocations of the extremities, shoulders, and pelvis region, followed by head and neck trauma, which often were of the greatest severity.

Rescue in the alpine of such severely injured patients is no easy feat– 94.6% of the accidents reported in the IATR required a helicopter evacuation. Bouldering injuries, on the other hand, were far less likely to require rescue. Of all the calls received by the Rocky Mountain Rescue Group over a 14-year period in Boulder County, Colorado, only 7% were from boulderers, while 55% were from victims who were roped.

So, in the end, what was the verdict on safety? Would one rather be chronically suffering from the sprains and strains of the hands and fingers while wrestling pebbles close to the ground, or risk the extremes of multisystem trauma for the love of great heights? Perhaps the best approach was to stick to strictly top roping indoors with a GriGri or using the auto-belays (Fig. 6). There may not be one straightforward answer for everyone. But this review of the injury patterns and mechanisms of bouldering versus rope climbing will hopefully provide insight for both clinicians and climbers on the different risks inherent to the sport.

[4] cases with injury severity score ≥ 16

[3] Other activities recorded in the registry included backcountry, mountain biking, snowshoeing, canyoning, and paragliding.

[2] Belaying (as well as finding a reliable belay partner) is an additional skill required when climbing with ropes. It is the act of managing the rope to which the climber is attached to protect them from large or dangerous falls. There exists a myriad of different belay devices to choose from, with varying techniques and safety mechanisms (Fig 3, 4, and 5).

[1] The Union Internationale de Associations d’Alpinisme [UIAA] scale was used to grade severity of injury. 1: mild injury or illness, no medical intervention necessary; 2: moderately severe injury or illness, not life threatening, outpatient therapy, heals without permanent damage; 3: major injury, not life threatening, hospitalization, surgical intervention, heals with or without permanent damage; 4: acute mortal danger, polytrauma, alive with permanent damage; 5: acute mortal danger, polytrauma, death; 6: immediate death)