Photo credit: W. Green, M.D.

Introduction

The hand is minimally protected and easily injured from trauma. It is made up of 27 bones along with nerves, arteries, veins, ligaments, tendons, muscles, and fingernails. Hand trauma is divided into five categories:

- Lacerations

- Fractures and dislocations

- Soft tissue injuries and amputations

- Infections

- Burns

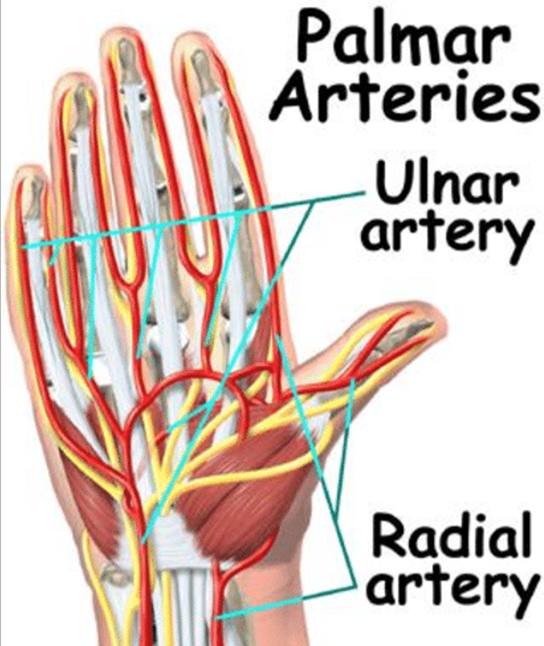

Blood vessels in the hand (see detailed overview) are vulnerable to lacerations since the radial and ulnar arteries feed each finger with arteries that are on both sides of the finger (see figure below). When lacerations occur to finger arteries, effective hemorrhage control is paramount. Thus, it is our intent to provide an overview of lesser-known treatment options for moderate to severe finger bleeding using a specifically designed commercial digit tourniquet (TQ).

Incidence of Finger Lacerations in Civilian and Austere Settings

Civilian

US emergency departments (ED) frequently manage finger lacerations from many causes. In a 20-year review, one study reported that approximately 45,000 finger amputations occur per year in the US with an incident rate of 7.5/100,000 people. An epidemiology study reported that finger laceration was the most common injury to the upper extremity with 221 per 100,000 annual ED visits over 4 years. More recently, a 5-year epidemiology study (2015-2019) using data from the National Electronic Injury Surveillance System database identified the leading objects causing finger lacerations: knives (31%), metal containers (4.2%), drinking glasses, cups and mugs (3.8%), doors (3.4%) and tableware accessories (3.4%).

Austere Environments

Military: A retrospective chart review of ED visits for noncombat-related hand injuries was conducted during a 2-year period in a combat zone. The top five noncombat activities causing injury to the hand were: 1) closing a hatch, door or turret; 2) cutting with knife or saw; 3) blunt force; 4) weapons use; and 5) sports. Another study conducted a retrospective review (2001 to 2018) of combat-related extremity injuries. Blast weaponry (75%) was responsible for the majority of upper extremity injury, followed by gunshot wounds (20%) to the shoulder and upper arms (37%), elbow and forearms (29%), and hand, wrist and fingers (33%).

Wilderness: In a review of wilderness injuries, the most common morbidities to upper and lower extremities are: 1) contusions; 2) abrasions; 3) lacerations; 4) sprains; 5) strains, and 6) fractures. The following table shows the incidents of lacerations range from 6 to 18 % of all injuries recorded in these various injury studies, and are replications of what has been reported for the past 30 years.

|

Reference

|

Population

|

Study Duration

|

Injury Incidence

|

Most Common Injury Locations

|

Top 5 Injury Type

(%)

|

|

Wells FC, Warden CR 2018

|

Students in Northwest Outward Bound Expeditions

|

~2.5 years

|

1.64 per 1000 program days

|

Ankle, knee, foot, hand, back

|

Sprain/Strain (46); laceration/puncture (18); wound infection (8); blister (4); head injury (4)

|

|

Stanford KA et al. 2017

|

Students and staff in NOLS expeditions

|

28 years

|

0.49 per 1000 person-days (2012)

|

All soft tissues-related incidences

|

Cellulitis/rash (25); lacerations/ punctures (18); burns (9); insect bites (9); blisters (8)

|

|

Nathanson AT et al. 2010

|

Survey of dingy and keel boat sailors

|

12 months

|

4.6 per 1000 sailing days

|

Leg; hand; knee; arm

|

Leg contusion (11-13); hand lacerations (6-8); arm/knee contusions (6)

|

|

Flores AH et al. 2008

|

Retrospective review of outdoor injuries treated in US EDs

|

12 months

|

72.1 per 100,000 annual

|

Upper and lower extremity; head and neck

|

Fractures (27); sprains and strains (24); lacerations (15); contusion/abrasion (16); TBI (7)

|

Management of Moderate to Severe Finger Bleeding

Extremity TQ application for severe bleeding in combat casualties has been a 20+ year success story. The Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) guidelines for TQs and other hemorrhage control techniques have successfully transitioned to civilian EMS and law enforcement. However, these TQs are not designed for finger application.

Improvised and commercial finger TQ

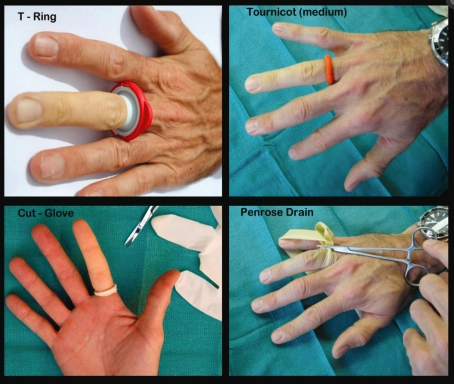

For over four decades, surgeons and physicians have proposed improvised finger (digit) TQ options. One recommendation has been to use a latex single-digit cut from a surgical glove; the glove finger is rolled proximally to the base of digit to create a ring TQ with pressure to control bleeding. There have been many other improvised finger TQ options, e.g., latex finger strip and nylon zip tie combination, Penrose drain, surgical glove rolled finger with hemostat clamp, adjustable nylon pipe gasket, and a fenestrated latex TQ for venipuncture that is applied to single or multiple injured digits. Importantly, studies have reported exceedingly high finger pressures with some improvised finger TQs. One study reported physiological assessment of finger TQ pressures and revealed that 150 mmHg pressure is sufficient to occlude arterial finger blood flow, but they should not exceed 300 mmHg pressure to prevent soft tissue and neurovascular injuries.

There have been decades of scrutiny for using a surgical glove rolled finger TQ option due to inadvertent failure to remove them following surgery that resulted in complications ranging from finger ischemia, irreversible digit narcosis, and amputation. The United Kingdom’s National Patient Safety Agency released a report in 2009 recommending the discontinuation of rolled surgical glove finger TQ due to 31 cases of digital injury. More recently, a revised rolled surgical glove finger TQ (includes video demonstration) that was designed to avoid the risk of removal failure and complications. The figure below shows two commercial and two improvised TQs.

Photo credit: S. Lahham.

To avoid these TQ complications, commercial finger TQs have been designed to be bulky and colorful so they catch the eye for removal. There are currently four commercial finger TQs for short-term use (<90 minutes recommended) to control bleeding and for initial wound management in austere settings, during EMS evacuation, in the ED, and for surgery. These four commercial TQs (see table below) are currently available with videos that present how they are applied. In several studies, the T-Ring TQ consistently shows low finger pressures (mmHg) when assessed on various finger sizes, but not all commercial TQs have been evaluated.

Implication for the Wilderness Medicine Provider

Since finger lacerations are common in the austere settings they can be effectively managed with an improvised or commercial finger TQ. It is important to note that not all improvised or commercial finger TQs report efficacy and safety evidence. Furthermore, any improvised or commercial ring style finger TQ that has to roll on from the fingernail to the finger base, e.g., Tourni-Cot, etc., becomes impractical to place on a traumatized finger. To date, only the T-Ring has peer-reviewed clinical evidence-based outcomes when applied to traumatized fingers; they are able to be pulled and stretched to easily place on any traumatized fingers and toes. T-Ring TQ finger pressures are consistent across different fingers and are well below the critical soft tissue pressures known to cause neurovascular morbidities. Another advantage of the T-Ring TQ is that this company offers a wound management kit (T-Ring TQ, wound closure mesh, topical lidocaine 2% gel, sterile gauze, benzoin ampule, and scissors).

A reasonable improvised alternative to the T-Ring TQ is to use a latex finger strip from a glove or a latex venipuncture band that is wrapped around the base (palmer to dorsal hand sides) of a bleeding finger and then pull each end with light pressure before securing with a hemostat clamp. By using a hemostat to secure, the latex band pressure can be adjusted so it is not too light (<150 mmHg) or too tight (>300 mmHg), ensuring ideal pressure for bleeding control. The figure below is an example of this technique.

Photo Credit: Brian Lin, MD

Final Thoughts

Being prepared for finger trauma with an improvised or commercial finger TQ is strongly recommended for effective bleeding control and wound management. However, some commercial finger TQs are more practical for rapid application to a traumatized finger when used in an austere setting. When considering to use an improvised or a commercial finger TQ, it is recommended to select one so it can be self-applied to your own injured finger, or applied easily to a patient by a first responder with no training. Since these finger TQs are small and lightweight, as well as low cost, they can be easily added without bulk to residential, occupational, combat, or wilderness first aid kits.

Disclaimer:

The authors have no conflicts of interest with any products in this article.