INTRODUCTION

Wilderness medicine is characterized as “remote and improvised care of patients with routine or exotic illnesses or trauma, limited resources and manpower, and delayed evacuation to definitive care.” This is similar to battlefield medicine and why there has been a close relationship between operational military medicine and the WMS for decades.

These conditions often occur during remote accidents related to traffic, commercial, or wilderness/adventure mishaps. Medical care is compromised by several key complicating factors including: terrain, injury type, weather, distance and time from medical facilities, and medical equipment/experience of responders. Care strategies range from “scoop and run” to Selective Prehospital Advanced Resuscitative Care (SPARC). This latter topic was discussed previously in Wilderness Medicine Magazine and emphasizes the importance of decreasing the interval between injury and lifesaving interventions for non-compressible torso trauma.

I recently participated in a medical/humanitarian mission delivering medical equipment and casualty care seminars to military medical personnel in the Donetsk region situated 10 miles from the front lines of the Ukraine/Russian war. The normal chain of survival for a battlefield casualty is: initial care from combat medic if possible, transport from the point of injury (POI) to a casualty care unit (CCU), transport to a short-term (1-2 days) hospital, then to a long-term hospital in Ukraine if needed.

THE BATTLEFIELD PROBLEM

At the CCU, I was surprised to learn the immensity of another key complicating factor specific to battlefield medical care – enemy fire. Casualties may lie at the POI for up to 10 hours. Indeed, if the enemy knows where a casualty is located, they can jeopardize all three phases of Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC). For example, the day I arrived, three battlefield casualties had lain at the POI all day until four evacuation medics reached them. All four rescuers had received worse combat injuries than their casualties.

The challenges of combat casualty care

- Limited tactical medicine training for non-medical personnel

- Delayed battlefield care and transport to medical facilities – up to 10 hours unprotected from the elements at the POI presents a significant cooling stress on the casualty

- Increased injury risk for evacuation personnel

- Limited or inadequate medical supplies at all levels ranging from the soldier, to medics, to CCU – many soldiers require improved first aid kits with proper tourniquets and hemostatic gauzes

- Limited medical training for paramedical staff at CCUs – a “trauma nurse” may only receive 2 days of tactical medicine training

- Persistence of medical myths (addressed below)

- Inadequate quality and improper use of tourniquets

DELIVERY OF EQUIPMENT AND KNOWLEDGE

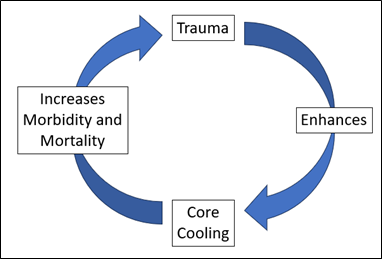

Based on my expertise and equipment requests, main delivery items were >1,000 TCCC-approved tourniquets and items to prevent hypothermia. The “triad of death” resulting from interactions between hypothermia, acidosis, and coagulopathy, is exacerbated by trauma. Main teaching points were that trauma enhances core cooling which itself increases morbidity and mortality from trauma (Figure 1). Thus, in cold weather, traumatic injury can quickly escalate from treatable to life-threatening. This principle even applies in summer when a casualty may be exposed for 10 hours on the ground. Preventing hypothermia is crucial.

Figure 1. Interaction between trauma and core cooling.

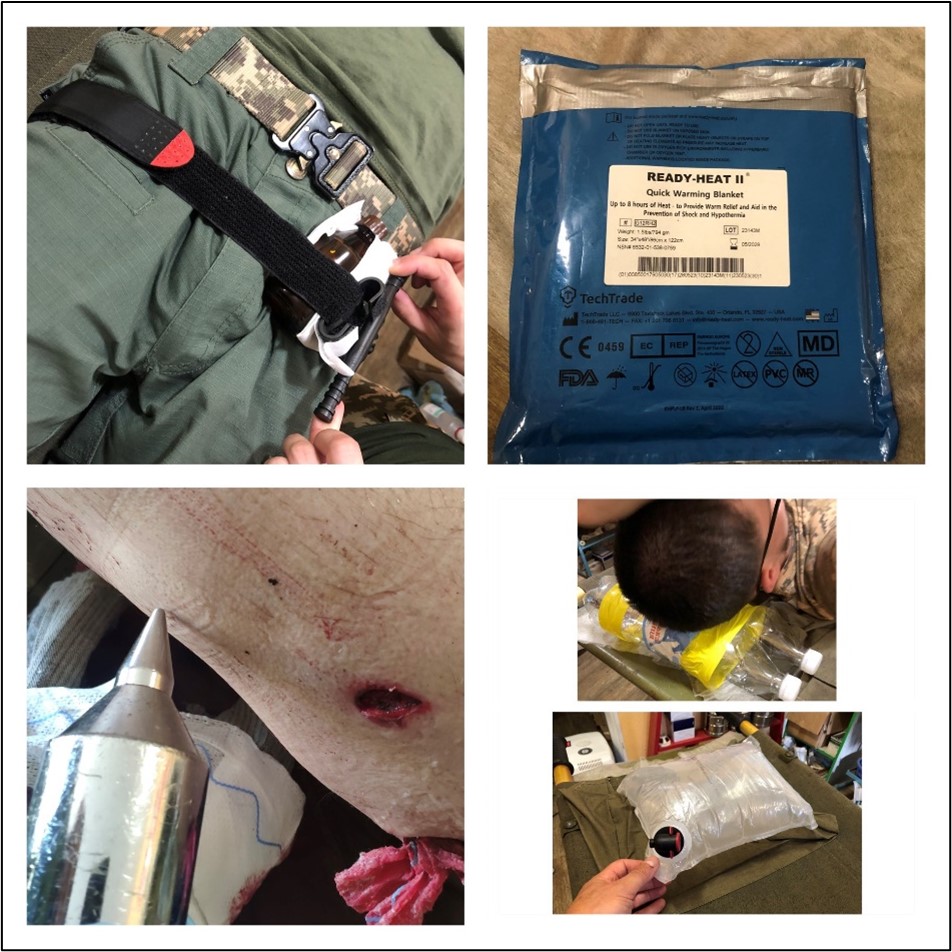

Ukrainian military personnel are familiar with MARCH (Massive hemorrhage, Airway, Respirations, Circulation, Hypothermia and Head injury). Instruction in the casualty care seminars included the greater prioritization of hypothermia. Thus, training included application of the Hypothermia Prevention & Management Kit, and how to improvise a hypothermia wrap if only individual chemical heating blankets were available. Medics were given the Cold Card (translated into Ukrainian) which advocates applying heat to the thorax. Medics were advised to apply heat under the body armor (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Heat source placed under body armor. (Credit – G. Giesbrecht).

While this information was well received by the participants, several cold-related myths were prevalent.

MYTHS THAT STILL PERSIST AND INFORM IMPROPER MEDICAL CARE

- 70% of body heat is lost from head. It was clarified that although the head should be insulated, a casualty cannot become hypothermic through the head.

- Apply heat to the head and feet. This is possibly related to misinformation about head heat transfer.

- Apply heat to the abdomen. This was to warm most internal organs. It was pointed out that the heart (the organ most at risk with hypothermia) is warmed more quickly via the axillae and chest.

- The level of hypothermia can be determined based on how proximally on the arm that oxygen saturation can be measured. This bizarre advice had no rationale or practical application and was easily discounted.

- Apply boiling water in bottles to armpits. While the location is best for heat transfer, burning the skin must be avoided. The provider should be able to place their hand in the water without burning their own skin.

THE TOURNIQUET CONUNDRUM

Although military personnel recognize that tourniquets are valuable to stop massive hemorrhage, several problems were prevalent in the supplies used by the Ukrainian military.

- Tourniquet quality. Many poor-quality tourniquets have been delivered to Ukraine. Some models fail. Medics were informed that TCCC has only approved the CAT-7 and SAM XT tourniquets.

- Tourniquet use. The indoctrination of tourniquet-use has led to misuse for non-arterial bleeding. One casualty appeared at the CCU with a fragmentation wound to the right ankle and a small non-bleeding puncture wound to the left thigh. Tourniquets had been applied to both thighs. The left tourniquet was not necessary.

- There are numerous cases where tourniquets are left on for up to 8 or more hours, resulting in loss of limbs. It is important to educate personnel on how to assess and convert the tourniquet within two hours per TCCC guidelines to prevent irreversible hypoxic tissue damage.

APPLYING WILDERNESS MEDICINE ETHOS TO BATTLEFIELD CARE

Figure 3 illustrates several ways in which the CCU personnel have adapted materials either for alternate purposes or to extend product life.

- Multiple tourniquets can be attached in series to create a pelvic stabilizer. A junctional tourniquet can be created by placing a liquid-filled bottle or other non-compressible object under the makeshift pelvic stabilizer.

- Dry chemical heating blankets (e.g., Ready Heat II) require air-exposure to provide heat for 8-10 hours. Since heating is often necessary for a much shorter period, the blanket can be resealed in its package. It can then be used several times over an extended period.

- A large magnet has been used for detection and removal of shrapnel.

- Pillows and supports were fashioned from empty water bottles or juice bags which allow thickness adjustment.

Figure 3. Equipment adaptations. (Credit. G. Giesbrecht/I. Kononenko).

CONCLUSION

Lessons learned from history tell us that it is very difficult to reliably pass these lessons on to a new generation; they are forgotten and then need to be relearned. There are many sources of up-to-date information and guidelines available to assist in combat medical care. Efforts need to be made to eliminate outdated sources of information and replace with current sources. Education needs to infiltrate all levels of training along with timely updates to prevent degradation of knowledge and skills.

Finally, in a war where billions of dollars are spent on weaponry, it should be recognized that a very small fraction of this amount could more than adequately equip soldiers and medical care providers at all levels with proper equipment and training to decrease battlefield morbidity and mortality.

Please click here if you are interested in learning about one way to help with efforts in Ukraine.