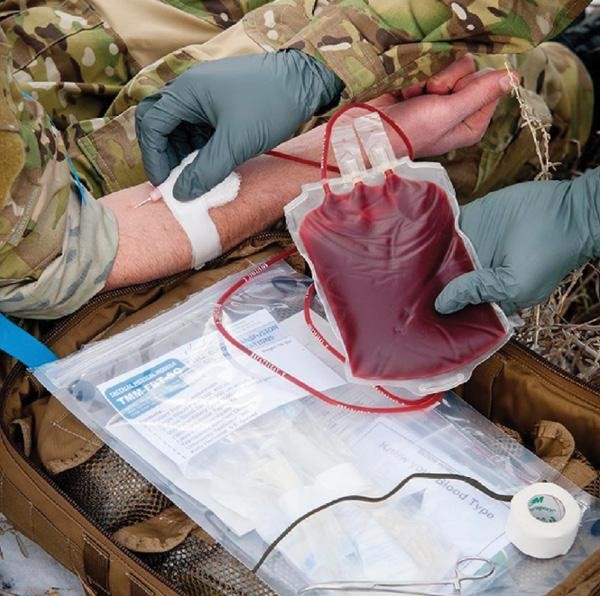

Photo credit: Phillip C. Spinella MD, THOR Network Foundation

Introduction

Recently, trauma subject matter experts (SMEs) from civilian and military sectors proposed a nationwide strategy for decreasing potentially preventable prehospital death (PPPD). Based on excellent precedence for military to civilian transition, these SMEs reviewed the evidence from the past 20 years of battlefield trauma strategies. The new civilian strategy is called SPARC (Selective Prehospital Advanced Resuscitative Care). These SMEs propose to use highly specialized clinical teams (e.g., physicians, nurses, paramedics) nationwide to deploy in urban and rural areas to provide advanced resuscitative care (ARC) and hemorrhage control near the patient.

Thus, our intent for this SPARC overview is multifold:

- State the rationale for this new prehospital trauma proposal that aims to decrease the incidence of PPPD;

- Describe the proposed strategy for the specialized trauma teams;

- Provide awareness for advanced wilderness providers and wilderness EMS directors to increase their knowledge about this new strategy, and help them to be part of the regional solution; and

- Establish a dialogue about SPARC capability extending beyond the urban and rural settings to selective patients in the wilderness.

Background

On the battlefield, penetrating trauma with massive hemorrhage is a leading cause of death. Consequently, many casualties die from exsanguination at the point of injury (POI) with the largest number of deaths occurring before they reach clinical intervention. Even if the wounded person reaches a hospital, many deaths occur within hours from irreversible shock complications before corrective surgery. Thus, the goal for the last 20+ years of the US military trauma system has been to decrease the PPPD on the battlefield and at receiving combat hospitals by reducing the time between injury and lifesaving interventions.

Some Department of Defense (DoD) strategies to improve combat care at the POI have been to:

- Implement extremity hemorrhage control procedures, e.g., tourniquet, hemostatic gauzes, wound packing, and pressure dressings into the Tactical Combat Casualty Care (TCCC) guidelines;

- Implement advanced resuscitative care (ARC) procedures into TCCC; and

- Place tactically mobile, small surgical teams far forward on the battlefield.

These interventions are just part of the 20-year success story in combat casualty care within DoD due to unprecedented decreases in PPPD, and the decreases in case-fatality rates in Afghanistan and Iraq (2001-2017).

Given these DoD successes, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) developed a team of military and civilian trauma SMEs to partner together with a goal to release a national trauma action plan in an effort to achieve zero preventable deaths. The key rationale for this nationwide effort, as stated in the 2016 NASEM report, is that approximately 20% (30,000) of the 150,000 deaths US civilian deaths per year may have been preventable with optimal trauma care at the right place and at the right time.

Selective Prehospital Advanced Resuscitative Care (SPARC)

In an effort to achieve the NASEM nationwide trauma goal, the SPARC strategy was proposed in 2022 by Dr. Z. Qasim MD, the team leader of the military and civilian trauma SMEs. He states that great in-hospital advances have been achieved by lowering civilian trauma mortality with damage control resuscitation and surgery, but decreasing mortality in the prehospital setting has not really improved. The SME rationale for the SPARC trauma proposal was the following:

- The proportion of annual prehospital and early in-hospital potentially preventable deaths (~20%) is likely underestimated as previously reported by NASEM and can vary widely throughout the US (between 29-45% based on recent data).

- Patients who will benefit the most from rapid ARC intervention have noncompressible torso hemorrhage (NCTH), where prehospital EMS interventions and resuscitation focus on extremity hemorrhage. The current prehospital hemorrhage control approach is too one dimensional to significantly decrease PPPD nationwide to achieve zero preventable deaths in the future.

- Injury severity and time elapsed from the POI until ARC intervention are tightly linked to hemorrhagic death. In the prehospital setting, death from severe NCTH can occur within 30 minutes, and if the patient survives at the POI, the initial peak of in-hospital deaths occurs within the first to second hours from hemorrhage complications.

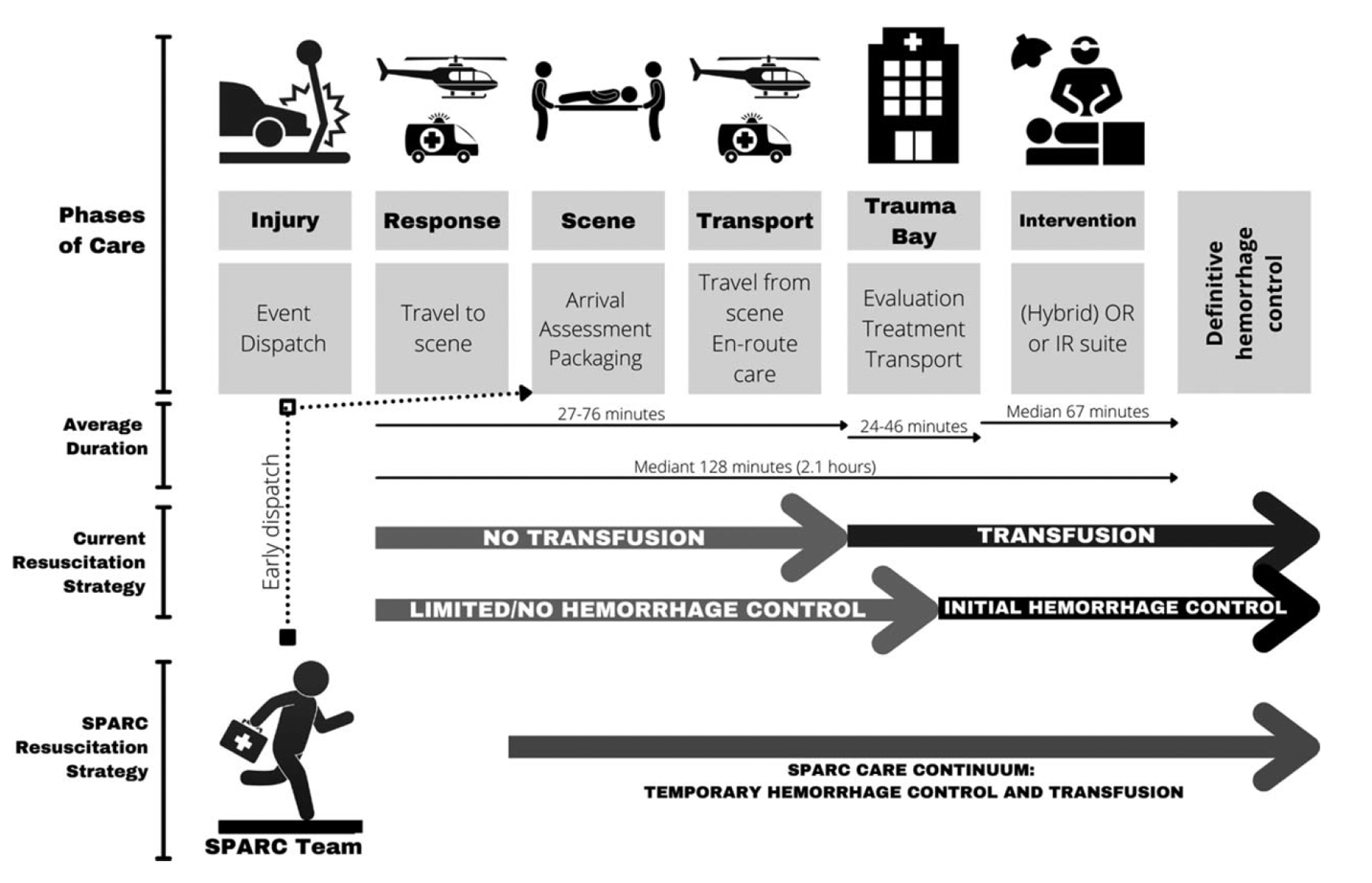

- Based on multicenter study data from US trauma systems, the average time from POI to surgical hemorrhage control is approximately 128 minutes (See Figure 1). Thus, in-hospital surgery for these patients is often applied beyond the point of irreversible hemorrhagic shock.

Based on this rationale, Dr. Qasim and the SMEs stated there is a need for existing trauma systems in the US to adapt so that life-saving interventions for selective patients with NCTH can be delivered closer to the POI. It is their opinion that the older concept in EMS to “scoop and run” philosophy is not multi-dimensional, and in many cases within highly dense urban and austere rural settings, there have been significant delays getting the patient to definitive hospital care. In these cases, the SPARC teams would work within a trauma system to deliver ARC and hemorrhage control for NCTH at the POI and continue during transport to in-hospital surgical care (Figure 1).

There is a great precedent for the mobile SPARC team concept that has been successfully demonstrated in military units with far forward ARC on the battlefield:

- U.S. Air Force (USAF) Special Operations Teams (i.e., Pararescuemen) along with forward deployed surgical teams;

- The Medical Emergency Response Teams within the United Kingdom (UK) military.

More recently, the USAF has developed a multidisciplinary clinical team called Tactical Medical Augmentation Team, which is made up of an adaptable medical capability based on requirements that consist of either two to six individuals (e.g., physicians, nurses, and paramedics). Furthermore, in the European civilian sector, the concept of SPARC teams comes from London’s Air Ambulance, and in France, the Service d’Aide Medicale Urgente. Both UK and French ARC teams are physician-based teams that work in urban environments for daily ARC capability at the POI.

The SPARC team capability would be similar to existing DoD, UK, and French rotary-wing teams for on-scene and en route ARC interventions (e.g., IV/IO drug administration, extremity hemorrhage control, advanced airway management, thoracic hemorrhage control, pelvic fracture management, whole blood or blood components transfusion, and NCTH management with resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta, or REBOA).

Figure 1. The selective prehospital advanced resuscitative care (SPARC) continuum from prehospital point-of-injury extends en route to definitive care. Photo Credit: Zaffer Qasim MD

Final Thoughts

The SPARC proposal is ambitious and not without many challenges, but the developers are confident it is achievable since the concept is well-established in the UK, France, and elsewhere. When urban and rural SPARC teams are jointly located in a robust regional trauma system, the potential ability to extend into the wilderness is probably achievable for these select patients requiring ARC intervention. Currently, there are many Federal, State, County, and City EMS aeromedical assets used for patient evacuation from either urban, rural or wilderness trauma settings. Some critical care aeromedical assets that could be adapted to a SPARC team capability are located within Level 1 and 2 trauma centers in, e.g., Salt Lake City, Utah; Jackson, Wyoming; Phoenix, Arizona; San Bernadino, California; Portland, Oregon; Seattle, Washington; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Hanover, New Hampshire, among others. These specific communities are just a few examples that are surrounded by wilderness (i.e., forests, mountains, or deserts) and have vast recreational activity. The ultimate challenge will be the maximal range, terrain access, weather, etc. that a rotary-wing SPARC team could respond to into the wilderness, and the time between the onset of severe injury and critical ARC intervention.