Arrgghh-I just can’t sleep!

Whenever or wherever we have to perform—demanding shift job, mountaineering expedition, even a well-deserved relaxing vacation, we need to get a good night’s sleep.

When at home in our normal routines, sleep often evades us—job and family stress, overworked bodies and brains, a pandemic going into the third year, too much blue light from electronics. We can try to escape from all of this to the wilderness—no email, work calls, or small screens (if you have the discipline to disconnect), tons of exercise, open spaces, blessed quiet, darker skies. But sleep still cannily dodges us—the rigors of travel to get there are exhausting and physically overstimulating. The weather can be too hot, too cold, too violent, too high, too dry, endless drives, being cramped on a ship, plane, or a crowded tent, crossing multiple time zones, traffic noise, trying to sleep with a midnight sun or trying not to sleep all day when the sun doesn’t rise, jitters about working in that underequipped rural hospital or that crux move on the climb, hearing an ominous snuffling outside the tent in the middle of the night… oh my.

Lack of sleep can lead to utter exhaustion, confusion, and lack of good judgment. Commonsense suggestions for getting racked out in the wilderness (works for home and hotel rooms too) include:

- Ensure adequate sleep duration for all (7-8 hours for adults, 9-11 hours for kids)

- Sleeping conditions should be as comfortable as possible—pillow, hat, dry clothes, earplugs, eyeshades, mellow music or podcast

- Avoid caffeine for 6 hours or more before hitting the pillow

- Avoid long naps

- Avoid alcohol as it interferes with REM sleep

- Wake up the same time at the destination as at home

- Avoid sedative sleep medicines

Give me something to help me sleep!

The world has a sleep problem (exacerbated by the Covid pandemic)—the global market value for the sleep economy is expected to climb to almost $600 billion by 2024, and includes a multitude of prescription or over-the-counter (OTC) drugs to coax weary humans into slumberland. While there are legitimate medical reasons for sedatives to be taken (e.g., sleep disorders, shift work), a basic personal traveler or wilderness medical kit should avoid these drugs, but instead can include an OTC sleep aid such as older antihistamines (the sleepy kind): diphenhydramine (Benadryl), doxylamine (Unisom), chlorpheniramine (Chlor-Trimeton). Prescription sedatives, such as benzodiazepines, can cause excessive drowsiness or the increased risk of DVT or falls during long flights, and consuming alcohol only potentiates these risks. Benzodiazepines commonly used for sleep include alprazolam (Xanax), temazepam (Restoril), lorazepam (Ativan), zolpidem (Ambien), zaleplon (Sonata), eszopiclone (Lunesta). Acetazolamide (Diamox) has been shown to aid sleep at altitude, but by a different mechanism than just the knockout effect.

Melatonin: The Vampire Hormone

Then there’s melatonin—the so-called “vampire hormone”, which seems to be everywhere these days. Exogenous melatonin was discovered in the 1950s and became available as a nutritional supplement in the 1990s. Used for many years for jet lag, melatonin has entered the mainstream as a sleep aid. Melatonin requires a prescription for certain age groups in Canada, Australia, UK, Europe, and Japan (and possibly others), with further restrictions in children; however, it is available in the US as an OTC “dietary supplement,” leaving the choice of whether to use the product up to the consumer (if it has not been prescribed by a healthcare professional for a diagnosed sleep disorder).

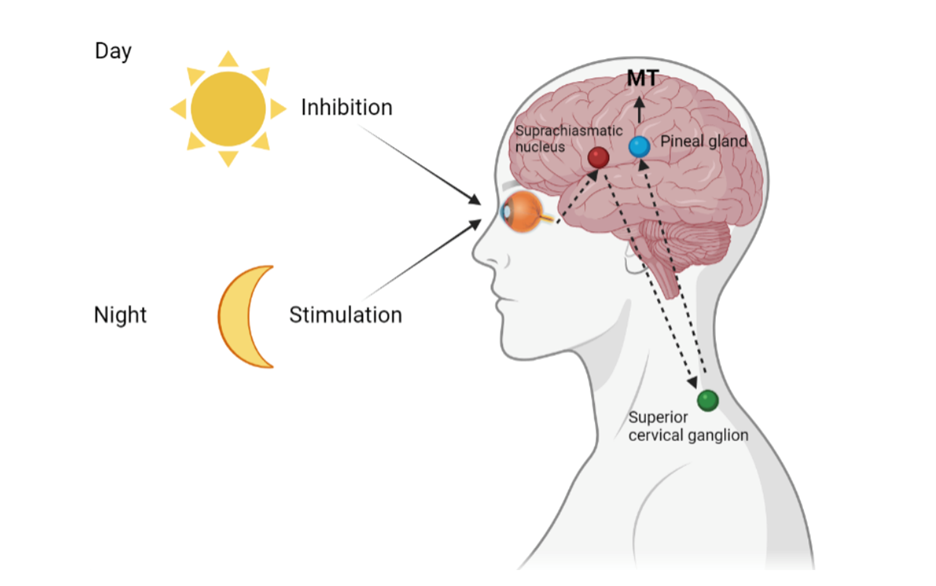

Melatonin is secreted by the brain’s pineal gland at night in response to darkness under normal light/dark conditions; naturally, it is inhibited by light (i.e, acting like a vampire). Not surprisingly, artificial nighttime lighting suppresses melatonin production, leading to more sleep troubles. The hormone stabilizes the body’s circadian rhythms of core temperature and sleep-wake cycles. [Figure 1]

Figure 1. How melatonin regulates circadian rhythm.

From: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/23/3/1835/htm

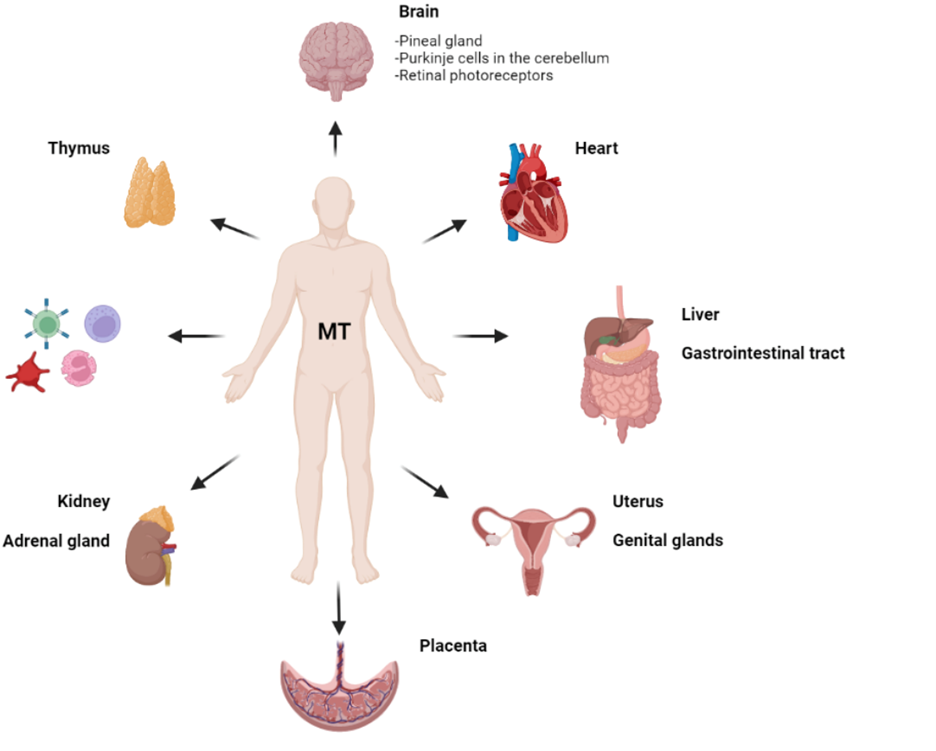

In addition, melatonin receptors are widely distributed throughout the body [Figure 2] and physiological effects are quite varied, including detoxification of free radicals and antioxidant actions; bone formation and protection; reproduction, cardiovascular, immune or body mass regulation; therapeutic effects in gastrointestinal and psychiatric disorders, and cancer. A search of “melatonin” on clinicaltrials.gov found over 700 studies with investigations into the hormone’s use for conditions as varied as breast cancer, concussion, multiple sclerosis, genital herpes, autism, ulcerative colitis, diabetes mellitus, and of course, for Covid (prophylaxis against infection in healthcare workers). Who knew?

Figure 2. Distribution of melatonin receptors in the human body.

From: https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/23/3/1835/htm

But how well does melatonin work to promote sleep?

While melatonin is recommended by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine for use in a variety of sleep-wake disorders, and for use in children whose circadian rhythms are “off schedule” or those with developmental disorders, its use for chronic insomnia in adults is not recommended because of lack of efficacy.

In an article in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, it has been suggested that melatonin works better as a chronobiotic, not a hypnotic, because peak levels occur 20-30 minutes after oral administration (decreasing sleep latency), but the half-life is 40-60 minutes, so the effect on sleep duration is not impressive; one meta-analysis of 17 studies bore this out.

Yet, a study using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) found that self-reported melatonin use by adults significantly increased from 1999-2000 to 2017-2018, across all demographic groups. Sales of melatonin in the US increased a staggering $500M+ from 2016-2020. The AASM concluded that even though they found the product is not that effective, “a majority of informed patients would be likely to use melatonin compared to no treatment… based on its availability and the widespread perception of melatonin as a benign sleep aid.”

Melatonin dosing

Suggested doses for melatonin (oral) for sleep and jet lag are:

Insomnia: 3-5mg in the evening

Difficulty falling asleep: 5mg 3-4 hours before sleep period x 4 weeks

Difficulty maintaining sleep: use controlled-release formulation

Jet lag 0.5-5mg HS

Eastbound preflight, early evening dose followed by evening dosing x 4 days

Westbound evening x 4 days when in new time zone

Some of the most commonly reported side effects associated with melatonin use include dizziness and sleepiness (surprise), nausea, and headaches. But it is non-addictive, unlike benzodiazepines.

Dosage forms of melatonin

A search on amazon.com for “melatonin” found a dizzying array of products on just the first page: dosage strengths of 300mcg (0.3mg), 0.5mg, 1mg, 2.5mg, 3mg, 4mg, 5mg, 10mg, 12mg, 20mg, 600mg (melatonin max); formulations including tablet, capsule, gummie, liquid, fast melting, nutra spray, kids, extended (controlled)-release, Dippin’ Dots, lozenge, chewable, and in combination with other sleepy things like lavender and chamomile. There are even melatonin-free formulas! Enough to put even Dracula to sleep at night. How does one know which one to choose? And to complicate things, a concerning 2017 study found that 31 OTC melatonin supplements were found to contain -83% to +478% of labeled melatonin content, making it all but impossible to figure out which is the safest and most effective.

Whatever happened to giving kids a glass of warm milk before bedtime?

In June of this year, this report from the CDC made news headlines: from January 2012 to December 2021, over 200,000 pediatric melatonin ingestions were reported to the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data System; the reports in 2021 accounted for almost 5% of all pediatric reports, compared to 0.6% in 2012. This is hardly a surprise, as after multivitamins, melatonin is the second most administered product to children by their parents. Serious outcomes and hospitalizations due to accidental melatonin ingestions increased in children <5 years old (five required mechanical ventilation and two died). This prompted the AASM to issue a health advisory on Sept 9, 2022 stating among other things, “Parents should select a product with the USP Verified Mark (produced in a facility following the Good Manufacturing Practice [GMP] standards) to allow for safer use.” However, this is a voluntary program, and only a handful of products have received the Verified Mark. Adults should select a verified product for themselves, too!

To sleep and perchance to enhance performance: melatonin for high-altitude pursuits

Of interest to the trekking and climbing communities, a recent perspective in the Journal of Travel Medicine suggested that melatonin’s antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and other physiologic effects may improve the oxidative stress and inflammatory processes associated with high altitude disorders. Melatonin’s positive effects on performance at altitude may also be attributed to improvement of jet lag (if travel was over several times zones), and improved sleep. More study is needed in this interesting area.

Alternatives to melatonin for sleep

Before you pack melatonin in that medical kit, try it at home to see if it works—don’t take a chance on tossing and turning all night before that deep sea cave exploration. If melatonin does not work for you (it gives me a giant headache every time), alternatives include melatonin agonists such as ramelteon (Rozerem) and tasimelteon (Hetlioz), available by prescription. Again, a trial with any sleep aid before travel is important.

The following foods have been suggested to contain melatonin: milk, pistachios, walnuts, eggs, tart cherries, fatty fish (tuna, salmon), rice, goji berries, oats, mushrooms, corn, and bananas, so a before-bed munchie might help.

If the zzzs just aren’t coming, there’s always a weighted blanket, purported to increase melatonin production in the body. But who wants to stuff one in an already loaded backpack!