Source: Askdrsears.com

The Society for Interdisciplinary Placebo Studies defines placebo effects as “changes specifically attributable to placebo mechanisms (e.g., the neurobiological and psychological mechanisms of expectations), whereas placebo response refers to all health changes resulting from administering an inactive treatment….” More simply put, the placebo effect/response happens when someone receives a treatment, whether it is a substance that is ingested, injected, inhaled, applied, etc. or a procedure (such as sham surgery) that has no inherent therapeutic effect, but the recipient perceives an improvement in their symptoms or physical condition. Theword placebo has Latin roots, meaning “I shall please”. Whether the “I” referred to the substance or procedure administered by a person to another or to the recipient believing it was working is debatable. Ancient societies and indigenous peoples have used various substances (in addition to prayer rituals and other ceremonies) over the centuries to create positive effects that may or may not be related to a specific action of the substance. Sugar pills were introduced into medical practice in the 1700s, and the first demonstrated effect of placebo was in 1799. Placebo was defined in an early 1800s medical dictionary to be “any medicine adapted more to please than benefit the patient”. The placebo effect became an accepted medical phenomenon in 1955 with the publication of “The Powerful Placebo” by Henry K. Beecher. Beecher is responsible for the oft-quoted placebo response of ~30%, which he derived from poor study methods, but this number still sticks. Placebo-controlled trials became the standard in randomized clinical trials in the 1960s. It has been argued that the placebo effect will only work with subjective conditions such as pain and psychological diagnoses (depression, anxiety), and it has been demonstrated that they are most effective for pain, insomnia related to stress, and nausea and vomiting associated with cancer chemotherapy. However, if you take a look at some of the most popular books on the placebo effect, which range from the scientific to the self-help to the profound, it seems to achieve startling results even in complex diseases such as cancer:

- The Placebo Effect: How You Can Use the Power of Placebo to Trick Your Mind and Improve Your Health

- You Are the Placebo: Making Your Mind Matter

- The Power of Placebo: How Our Brains Can heal Our Minds and Bodies

- The Belief Instinct: The Psychology of Souls, Destiny, and the Meaning of Life

- Addicted to Placebos: Understanding Science and Society

- What Placebos Teach Us about Health and Care

- The Placebo Effect: By Harvard University Press

- The Brain that Changes Itself: Stories of Personal Triumph from the Frontiers of Brain Science

- Suggestible You: The Curious Science of Your Brains’ Ability to Deceive, Transform, and Heal

- Cure: A Journey into the Science of Mind Over Body

- Mind Over Medicine: Scientific Proof That You Can Heal Yourself

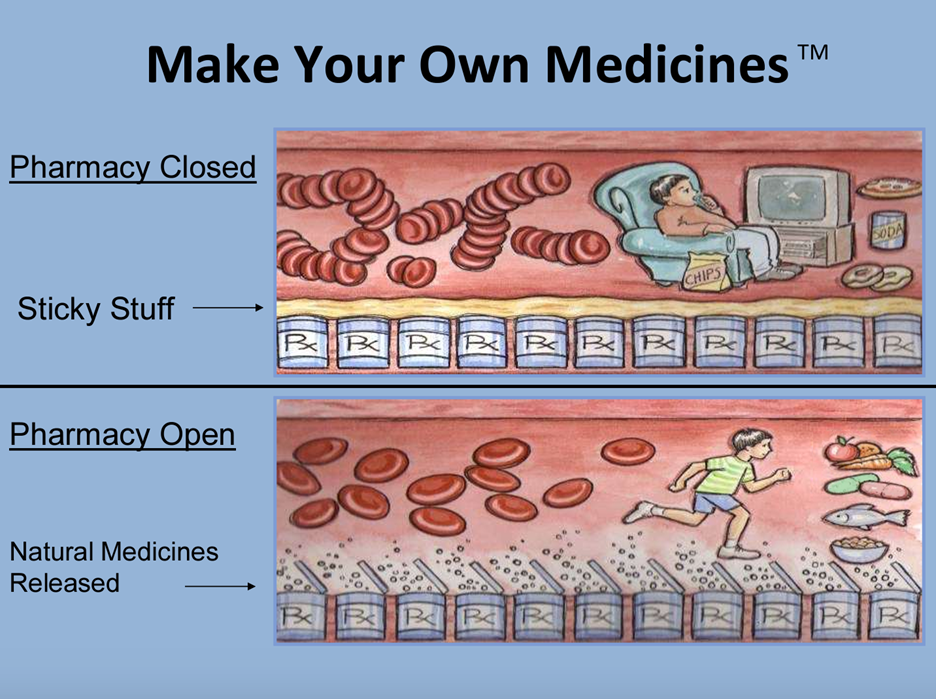

How does the placebo effect work? It may involve release of endorphins and dopamine. It may involve “expectation of clinical improvement and pavlovian conditioning”. It may have to do with increased activity in the middle frontal gyrus brain region. In any case, it just may work for whatever ails a person. However, there are ethical considerations when a doctor “prescribes” a placebo for a patient outside of a clinical trial without their consent (such as the M*A*S*H episode where the medics used donut sugar capsules when the morphine ran out). A pharmacy I used to moonlight in had us compound capsules filled with a mix of lactose and vitamin B6 for a doctor who used them in his recalcitrant patients – the vitamin made it taste “mediciney” and he believed the patients were none the worse for wear for it!

A well-known decongestant, pseudoephedrine (Sudafed), was recently taken off the market as it was deemed no more effective than a placebo. So did it not work for everyone all those years, or did it, and it was all in everyone’s head (or nose)?

There is also the converse of the placebo effect: the “nocebo effect” – believing that an intervention will result in a negative outcome, like an adverse effect from a drug. Is there an agnostic response – i.e., no response at all? Don’t know.

When would the placebo effect be of use in a wilderness setting? I could find very little in the medical literature that specifically addresses this, except in the context of placebo-controlled randomized trials, mostly for altitude illness. Of course, being out in and connected with nature makes you feel better in general, but what if you fall ill or fall and get injured? Packing a good medical kit with needed medical supplies, and drugs like antihistamines, analgesics, anti-inflammatories, antibiotics, antacids, antidiarrheals, etc., are key to staying healthy when things may go awry on a wilderness outing. But if these supplies or medications are not available, what are some other, non-pharmaceutical interventions that could help with healing or performance under stress?

- Herbal remedies – the contestant on Alone certainly would have benefited from a course of antibiotics for the infected spider bite. But in-depth knowledge and proper use of the plants certainly contributed to the clearing of the infection.

- Positive mental attitude – while working more slowly than traditional drugs, the contestant maintained an extremely positive attitude about the potentially serious situation; the psychological impact plus the use of plants enabled her to endure the pain and discomfort and perhaps aided in healing.

- Immune system boost – a positive attitude may also stimulate the immune system.

- Self-reliance – when an injured or ill person participates in their own care, like assisting a responder with applying a splint (or doing it themselves) or keeping ice on an injury, this may distract them and help in alleviating pain and stress.

- Meditation, mindfulness, deep breaths, and visualization (imagining a healed and pain-free body) may help immensely with pain and anxiety.

- Rituals and native healing practices – In Chapter 112 in Auerbach’s Wilderness Medicine 7th ed., “Native American Healing”, a traditional healer cautions us: ”Pollution begins in the mind”. As mentioned above, it has been well known for millennia that “the presence of the healer, quality of relationship between healer and patient, and faith of the patient are powerful influences on treatment outcome.”

- Presence in natural environments – also mentioned above, being in the outdoors has a very positive effect on human health, both physical and mental (see this recent article in Wilderness Medicine Magazine).

- Performance enhancement –a positive mental attitude (let’s all channel Ted Lasso) can also lead to increased physical performance – whether it is a patient who is injured or exhausted being able to summon the strength to aid in their evacuation, or achieving a high altitude summit with the help of herbal supplements claiming to help prevent AMS (i.e., if you don’t have AMS you’ll definitely feel and perform better).

Source: wildernessathlete.com

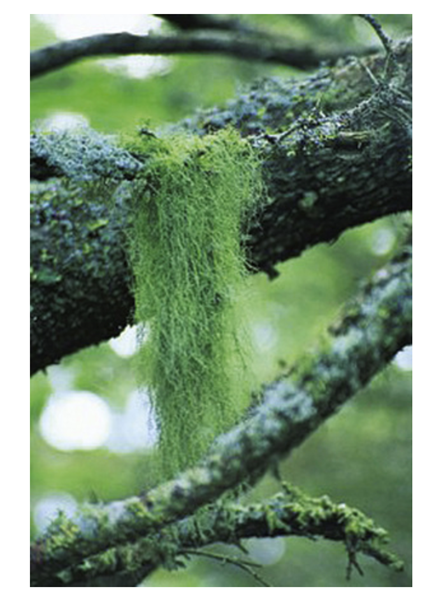

Interestingly, there’s a mention of Usnea (Old Man’s Beard) in Chapter 68 “Ethnobotany” in Auerbach’s text. Displaying antibacterial activity, the plant has been used in traditional medicine for many years to dress wounds. So maybe it was the lichen that licked the spider bites!

Old Man’s Beard (Usnea sp) Figure 68-25. From Auerbach’s Wilderness Medicine. 7th ed.