Most everyone has heard of “Mother’s Little Helper” – meprobamate (brand name Miltown) – a sedative popularized in the 1966 Rolling Stones song. Because of its abuse potential, including by housewives of folklore, it eventually became a controlled substance. In 2013, another accommodating drug was popularized in the outdoor literature in an Outside magazine story, “Climber’s Little Helper.” It was not about unhappy housewives, but an amateur climber who took wildly high doses of dexamethasone to enhance his chances of summiting Mt. Everest and his ensuing complicated medical issues. But is there really “rampant use of performance-enhancing drugs” (PEDs) in the mountains – rampant enough to have if not a song written about it, then a sensational story – and is dexamethasone really “dope”?

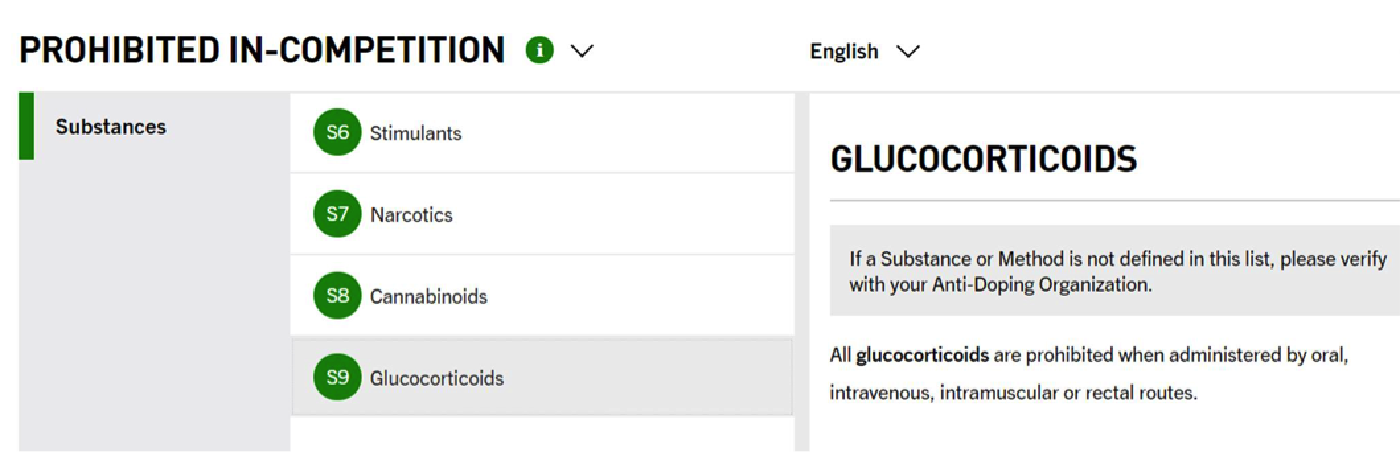

If “dope” is defined as “a drug taken by an athlete to improve performance” (Oxford English Dictionary), then yes, dexamethasone, a glucocorticoid prescribed for a number of indications, falls into this category. “Dex” is prohibited by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA):

Worldwide Anti-Doping Agency Prohibited List 2017

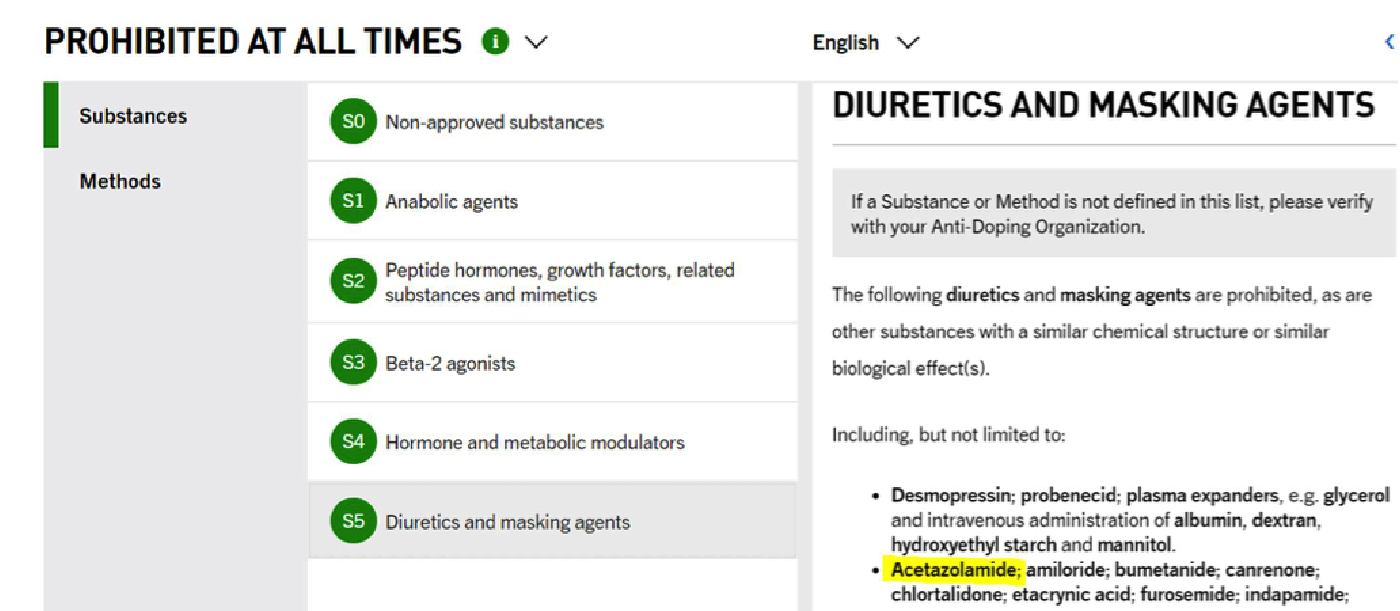

The same goes for acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor indicated for glaucoma but prohibited by WADA because it is a diuretic.

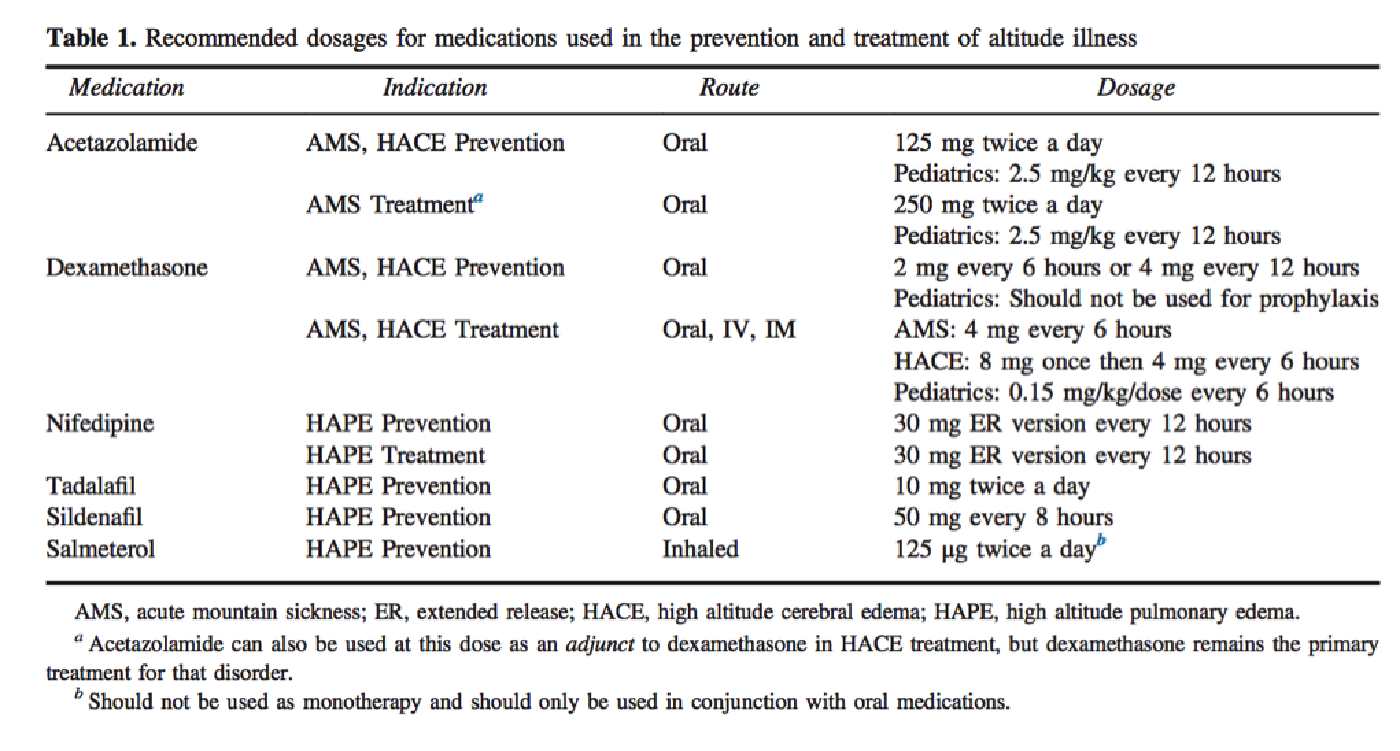

However, dexamethasone and acetazolamide are among the drugs recommended for the prevention and treatment of altitude-related illnesses by the Wilderness Medical Society.

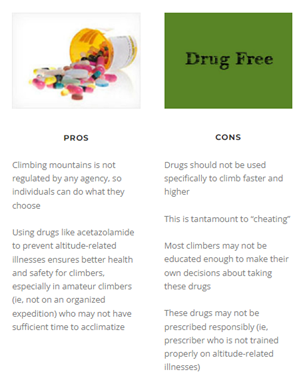

So should these drugs really be considered PEDs when taken during marches up mountains? It really depends on the setting (e.g., competition, organized expedition, leisure trekking) and whom you ask. The use of drugs to aid summit attempts has been around since early expeditions to Mt. Everest in the 1920s, so the debate has been smoldering – and occasionally erupting – long before the expose in “Climber’s Little Helper.” The editorial “Medical and Sporting Ethics of High Altitude Mountaineering: the Use of Drugs and Supplemental Oxygen” was published in Wilderness & Environmental Medicine in 2012 with an accompanying series of commentaries and there were definitely two camps on the issue.

Source:

http://www.wemjournal.org/article/S1080-6032(12)00103-2/pdf

http://www.wemjournal.org/article/S1080-6032(12)00194-9/pdf

Two documents from the UIAA (International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation-Union International des Associations d’Alpinisme), address the issue of “Drug Use and Misuse in the Mountains.” The medical professionals version was published in High Altitude Medicine & Biology in 2016.

A version for mountaineers and medical laypersons can be found here. This version can also be accessed from the UIAA site, which contains a number of valuable recommendations under their “Library of Recommendations” section.

The UIAA Medical Commission summed up their recommendations with the following statement:

“It is not the UIAA Medcom’s intention to judge. We simply welcome openness and honesty but also want to protect mountaineers from possible harm. We do believe that, wherever possible, the use of drugs specifically taken with the intention to enhance performance should be avoided in the mountains.”

-UIAA Medical Commission, 2014