71-year-old Steve Curry died on the afternoon of July 18 after collapsing in Death Valley National Park, where temperatures were recorded as high as 121°F. Curry, an avid hiker that had always wanted to hike in Death Valley, had left for the national park from his Los Angeles home without telling his wife. When interviewed about his motivation for hiking in such unforgiving conditions he responded, “Why not?”

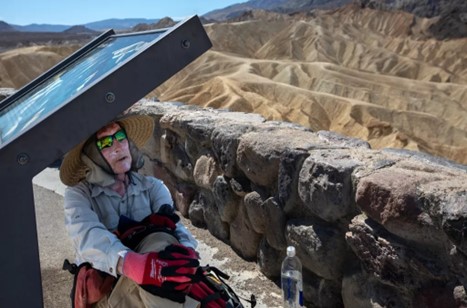

Steve Curry resting under a sign. Photo by Francine Orr, LA Times.

Around 10am on the morning of his death, he was found hiding in the shade underneath a sign at Zabriskie Point, Death Valley's most visited scenic overlook, by LA Times reporter Francine Orr. It had reportedly taken him two hours to hike half of the 6.1-mile loop from Golden Canyon to Zabriskie Point, but he claimed he was used to hiking in the heat and declined offers of assistance. Five hours later, he collapsed outside the restroom at Golden Canyon and despite resuscitation efforts, including an AED and CPR, he was unable to be revived by first responders.

Curry’s death, as well as that of a 65-year-old man found dead in his car with broken air conditioning in Death Valley, highlight the dangers of heat exposure, especially in elderly populations. Age-related changes in the skin such as poor blood circulation and less effective sweat glands, in addition to chronic medical conditions and polypharmacy, have been identified as some of the contributing factors that lead elderly people to be more susceptible to heat illnesses. In the US, heat is the number one cause of weather-related deaths. Core temperature can rise faster in older adults and a decreased thirst sensation complicates the risk of heat illness. These predisposing risk factors combined with physical exertion in hot environments can become a deadly recipe. Over the past 20 years, there has been a 57% increase in heat-related mortality amongst adults over 65.

The National Weather Service posts Excessive Heat Warnings and strongly suggests people avoid driving through these areas or going outdoors due to risk of death from heat exposure. While many urban areas offer free cooling centers for older people to avoid heat, this can be more difficult in outdoor settings. National parks have already experienced several heat-related fatalities this Summer. National parks visitor information websites frequently post weather advisories; Death Valley’s states “do not hike after 10am”.

If encountering someone showing signs of heat illness, the first task is to remove them from further heat exposure then to cool them down. Heat-related syncope, cramps, edema, rash, and exhaustion can be potentially reversed in a wilderness setting. However, prolonged heat exposure can lead to heat stroke, manifesting in confusion, seizures, or unconsciousness. Anyone who shows signs of heat stroke should be immediately evacuated.

Hospital systems can build resilience to extreme heat events by preparing Heat Response Plans in coordination with municipal agencies. The CDC has also developed an online tool that can map vulnerability within counties to ascertain each area’s available hospital beds to treat heat-related illnesses or trend past ED visits and hospitalizations for heat illness.