On Friday, June 23 a father and his two stepsons were hiking along the Marufo Vega trail on the east side of Big Bend National Park. When the younger son, aged 14, became ill and lost consciousness, his 21-year-old brother attempted to carry him back to the trailhead while the father hiked back for help. According to an NPS press release, park officials received a distress call at 6:00PM and a team of park rangers and US Border Patrol agents arrived at the scene along the trail at 7:30PM. The boy was unfortunately found deceased.

Adding to the tragedy is the death of the 31-year-old stepfather from a motor vehicle accident while attempting to coordinate rescue for his son.

This incident remains under investigation, with further details regarding the boy’s symptoms unavailable at this time. However, given the 119°F temperature at the time, his death is suspected to be heat related. It is unclear if the other two members of the party were suffering from heat-related symptoms as well. The lower elevations of Big Bend National Park, located in southwest Texas along the US-Mexico border, are known for extreme heat.

The Marufo Vega trail in particular is known for high temperatures. The National Park Service describes this trail as having “stark but stunning terrain”. It is a 14-mile loop trail with no shade, no water, 2000 ft of elevation gain in each direction, and no cell coverage. The trail is considered “potentially deadly from April through September”. There have been prior heat-related deaths on the Marufo Vega trail, most recently a 54-year-old-male on July 2, 2019.

Trail Sign. Photo by bigbendguide.com

Prevention

For heat illness, as in much of wilderness medicine, prevention is key. Heat acclimatization results in physiologic adaptations for hot weather, increasing efficiency of the body’s cooling mechanisms. In hot conditions, individuals should have access to shade, sun protection, rest breaks, and water. While a fully hydrated person can still get heat illness, dehydration is often a complicating factor in hikers who succumb to heat. Hikers should plan their activities according to weather conditions. Weather and temperature advisories are often listed on park websites and on trail signage.

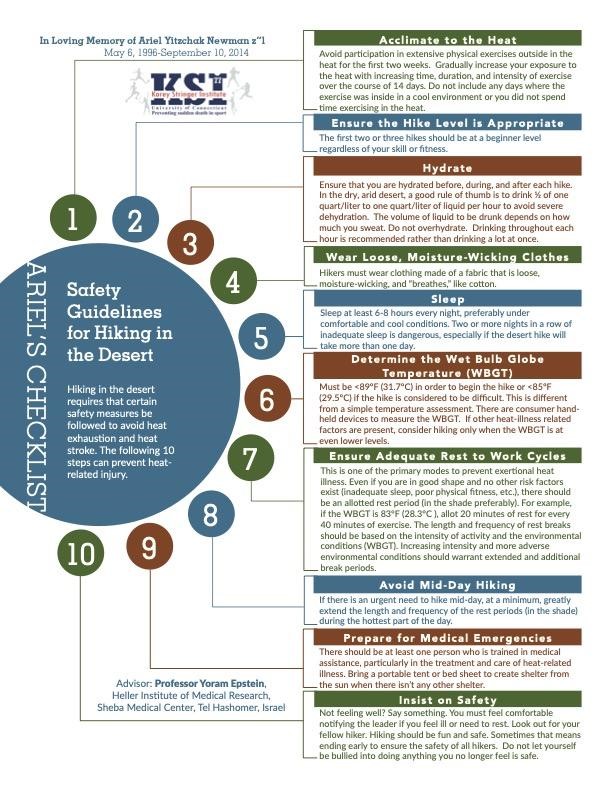

Public information campaigns, such as Ariel’s checklist, are resources that can be used to provide outdoor recreationists with easy-to-understand safety guidelines including acclimatization, proper clothing, avoiding mid-day hikes, and ensuring proper rest.

Ariel’s Checklist. From arielschecklist.com

Recognition

The key to good outcomes in heat related illness is early recognition. Common early symptoms can include headache, nausea, dizziness, cramps, and weakness. In the early stages this is called heat exhaustion. If not treated, heat exhaustion can progress to heat stroke, differentiated from heat exhaustion by symptoms of deteriorating mental status such as severe confusion, seizures, or coma. Rectal (core) temperature is at least 104°F, however, this is often not able to be measured in wilderness settings. Without proper treatment, this stage can lead to organ failure and death. Recognizing and treating heat illness as early as possible can prevent these catastrophic outcomes.

Treatment

When treated early, heat illness can be easily reversible. For milder forms of heat illness, place the individual in a cool, shaded area and encourage the person drink to replace fluids. Wet and fan the individual if possible. If available, place ice packs at the neck, groin, and underarms.

Heat stroke, while potentially deadly, has a high survival rate if the individual is cooled promptly. If core temperature is not available, progress can be measured by symptoms, particularly improvement of altered mental status. The most effective treatment for heat stroke is ice water immersion. This results in rapid cooling through the process of conduction. If an immersion tub isn’t available, an effective alternative is the “TACO method” (tarp-assisted cooling with oscillation), in which ice water is poured over a victim, who is wrapped, taco-style, in a tarp or blanket.

TACO Method. Photo from Colleague by the University of Arkansas

In remote areas, ice is not typically available, so rescuers may resort to the spray and fan method. Spraying (or sprinkling) victims with small amounts of water and aggressively fanning takes advantage of evaporative cooling. This method takes twice as long to cool an individual compared to ice water immersion; however, it can still be effective and requires fewer resources. For patients with heat stroke, cool as rapidly as possible and evacuate. Further information and recommendations on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of heat-related illnesses can be found in the WMS Clinical Practice Guidelines on Heat Illness.

At this time, there are limited details about the clothing, access to water, acclimatization, duration of the hike, and other information about the Big Bend hikers. We do know that the park website has an Extreme Heat Advisory on the homepage, advising hikers to be off trails in the afternoons due to dangerously high temperatures. Special recognition must also be given to the park staff and US Border Patrol agents who were able to respond to the scene promptly despite dangerous heat conditions.