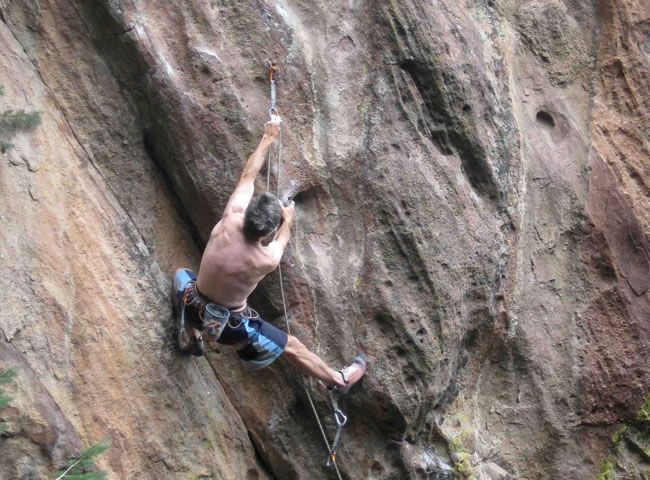

Climbing helped save Matt Samet's life. The fellowship of the rope − perfectly exemplified by the faith of his friend Andrew on the darkest of days - and the focus, strength, and mental agility required to walk the fine line between success and failure were among the factors in his very personal struggle with benzodiazepine addiction detailed in Death Grip.

A riveting personal account of a life of outward success and inner struggle, Matt Samet details his fight with anxiety, his downward spiral of addiction to benzodiazepines, and their effects on his climbing, his personal relationships, and his profession. Matt bares all in this gripping account of personal addiction, of hitting rock bottom and the slow, painful climb to overcome his addiction and regain his life. Interwoven within this narrative are his interactions with caregivers at all levels, a discussion of the marketing efforts by drug companies to provide medication for his ills, and the help of friends and strangers as he sought for a cure.

This engrossing tale of one man's fight to regain his life with the help of his family, friends, and particularly the empathy and understanding of Alison Kellagher, shows the power of the human spirit, that when given hope, can accomplish all things.

I actually first climbed when I was 12 years old in the mid-1980s with a family friend up in the Cascades in Washington. I loved it from the get-go and knew this was something I wanted to do more of, but at that time there weren't any rock gyms, so nowhere, really, for a kid like me to go to safely learn to climb. When I was 15, I was old enough to take a New Mexico Mountain Club basic-climbing class, and from there I've climbed three to five days a week every week, except when injured. As for journalism, I was a geology major when I started at the University of Colorado-Boulder because I figured, "I like rocks." I also suck at science and so balked at the prerequisites for a geology degree, and by sophomore year I had switched to journalism. I actually wanted to drop out of college and climb full-time, but my dad said, "What about when you're 40 and your fingers ache−do you want to be living in a van out at the rocks, with no profession? How about journalism? Then you can write about your climbing." I'm 41 now, and my fingers do ache a bit after 26 years of wear-and-tear, so I'm glad I listened to my pop and stayed in college. Once I graduated in 1996, I started doing some small articles for Climbing Magazine on the European competition and sport-climbing scene, and then moved more and more into outdoor journalism from there.

It was quite difficult−both in knowing how vulnerable I was making myself by sharing this story in detail, but also in trying to make it accessible in a way that framed my struggle precisely how I experienced it, and not within the very broken narrative of psychiatry. My truth, as I lived it, was that despite any personal "addictive" tendencies or whatever hand I myself had in my downward spiral, the misdiagnoses and poly-drugging foisted on me by psychiatrists as I struggled to break free of chemicals was profoundly damaging−nearly fatal. Had I stayed that course, I'd be dead now or at least so ill as to be nonfunctional. This, of course, flies in the face of the mainstream wisdom about what it is that psychiatry and these medications purport to do: treat "mental illness," which is allegedly some sort of "biological condition" (despite zero empirical proof of this much-touted hypothesis). However, talk to any survivor of psychiatry, and they'll likely have a story just like mine: a downward spiral of hopelessness, increasingly worse diagnoses, more and more pills piled on with a host of life-altering side effects, until eventually the person wakes up and finds the exit door. My hope was that in sharing this tale, even if there is some personal risk, if at least one person sees him- or herself in my struggle and avoids the same mistakes, then it will have been worth it.

I suppose I would say to view anyone who comes to you for medical care as a person first, and a patient second. The labeling, judgment, and dehumanizing we-know-what's-best "care" I received at the hands of psychiatrists turned me off to medicine in general for quite a while. The arrogance, the obliviousness to what I was saying, the forced drugging because I had a "chemical imbalance": these all represented a deep betrayal of trust. Only in the last couple years have I been able to trust the medical world enough again to even do little things like get a routine physical. I would simply remind anyone in a caregiver role to remember just how vital the human connection is first and foremost−to take the time to listen to their patients, to first do no harm.

The fact that Alison had been through it herself and came out on the other side was huge. Until then, I had only met other folks in hospitals, groups, etc., who were staying the psychiatric course, so were dutifully taking meds, sometimes as many as five or six at once, and buying into this paradigm of having a "lifelong condition." But when I finally met someone who said, "Look, what you're experiencing−this terror, this insanity−is exactly what I felt while in benzo withdrawal. And that that might be the real source of your suffering," I finally had hope for a normal, natural, chemical-free life if I just gave myself time to heal. All that the doctors could offer were more and more pills, more and more diagnoses, more and more control. But with Alison, there was someone offering hope for normalcy, saying, "I got better with time, and you will too. You just have to believe in yourself and the brain and body's desire for integral health." It was amazing.

I did my best, for sure. Dr. Ashton has written so well and with such clarity on the subject, through her various papers and studies, that it gave me a great foundation for explaining how benzos can affect the brain. I've also read plenty of other books on anxiety, psychiatry, psych meds, etc., so also had those to guide me. Dr. Ashton was kind enough to read rough drafts of the benzo sections and give scientific advice about the wording and so on. Invaluable!

Don't do drugs. Do climbing (hiking, rafting, kayaking, mountain-biking, skiing, backpacking, etc.) instead.

Thanks Matt, for your time and good luck to you and your family. We appreciate you taking the time to answer our questions.

Watch Matt Samet’s interview on February 2013 in Boulder, Colorado on KVCU’S radio program CLIMBTALK