“Respiratory paralysis? I don’t see that here. Show me some cases.” That was the response from Dr. Geoff Smelski, Director of Clinical Education at the Arizona Poison and Drug Information Center (APDIC) in Tucson, in early 2022 as I was preparing a new manuscript about identifying Mohave Rattlesnakes (Crotalus scutulatus). “Okay, no problem,” I replied.

Having lectured and written for decades about rattlesnakes, I knew well the warnings about neurotoxic Mohaves causing serious envenomations that look benign initially, only to potentially cause respiratory failure hours later. Finding a few cases for Geoff would be easy, or so I thought. But after combing through the literature, I was bewildered to find only one case report.

During my quest, I not only searched for mentions of respiratory failure and paralysis, I also pulled any references cited by those papers and backtracked through layers of references as far as possible – a search that took me back 90 years in the literature. To my surprise, one publication after another either listed no references, cited references that lacked strong supportive information, or cited similar warnings in previous publications – many by well-respected authorities. The one well documented case, published in 1992, described a young woman in California’s Mohave Desert who experienced prolonged respiratory failure following a confirmed Mohave rattlesnake bite. But only one case?

In the meantime, Geoff Smelski had just completed a detailed analysis of 3440 Arizona rattlesnake bites reported to APDIC between January 1999 and December 2020. He had enlisted the help of a team of reviewers who spent over 2½ years reading each case and entering all available information into a spreadsheet that grew to more than 120 columns. Geoff then verified each case himself. In both his data review and my literature search, we strived to differentiate neurotoxic respiratory failure or paralysis caused by weakness of the muscles of respiration from airway obstructions that typically occur during an allergic response shortly after the bite or administration of antivenom. There was no evidence of neurotoxic respiratory failure or paralysis in APDIC’s 3440 cases and we published those findings in January 2023. Coincidentally, another review of 289 Arizona rattlesnake envenomations also reported no respiratory paralysis.

As I traced back through the layers of references warning about respiratory paralysis, they attributed the danger most frequently to Mohave Rattlesnakes. I had long known about the Mohave’s undeserved reputation for being extraordinarily lethal, but was their reputed ability to cause respiratory paralysis unproven, as well? After all, I had passed that warning along to many audiences myself.

My deep dive into the literature eventually ended at a paper published in 1931 by Dr. Thomas Githens. He conducted some of the earliest lethality comparisons of pitviper venoms, using pigeons as test animals. He described “a so-called neurotoxin” that caused progressive paralysis that eventually reached the respiratory muscles, which produced death. Four years later, he reported that venom from Tiger Rattlesnakes (Crotalus tigris) and Mohave Rattlesnakes ranked highest in lethality among 27 North American pitvipers tested, producing “acute paralytic death” in pigeons.

Fresh Mohave Rattlesnake venom from a single extraction. Click here for extraction video.

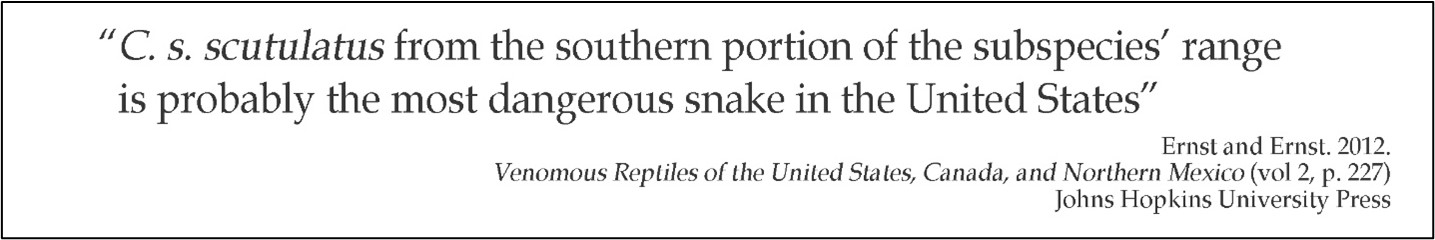

In 1956, Laurence Klauber quoted Githens in his highly acclaimed two-volume rattlesnake reference, Rattlesnakes: Their Habits, Life Histories, and Influence on Mankind, stating that if future tests corroborate the available lethality data of Mohave Rattlesnake venom, the species “…may prove to be a very dangerous rattler.” Indeed, future analyses over several decades did confirm the extreme lethality of neurotoxic Mohave Rattlesnake venom in mice. As a result, warnings abounded in the latter half of the 20th century – and into the 21st – in medical, biological, and non-technical publications, about the Mohave Rattlesnake’s extreme lethality and its potential to produce respiratory paralysis. Apparently unnoticed, however, was the scarcity of corresponding human clinical cases as the years passed.

Termed the “bad boy of rattlesnakes,” the reputation of Mohave Rattlesnakes for being extraordinarily dangerous has exploded, spinning off countless sensational rumors of the “Mohave green” having a mysterious recent origin, being an exotic hybrid, and even having been created by the U.S. government! Adding to this abundant but misleading folklore was the legitimate discovery in the mid-1970s that the species produces two distinct venom types. While Mohave venom is dominated by a phospholipase A2 neurotoxin throughout most of its distribution, a large area in Arizona, anchored by Phoenix in the north and Tucson in the south, was found to contain Mohaves that produce more typical rattlesnake venom dominated by tissue-destroying metalloproteinases and lacking the neurotoxin.

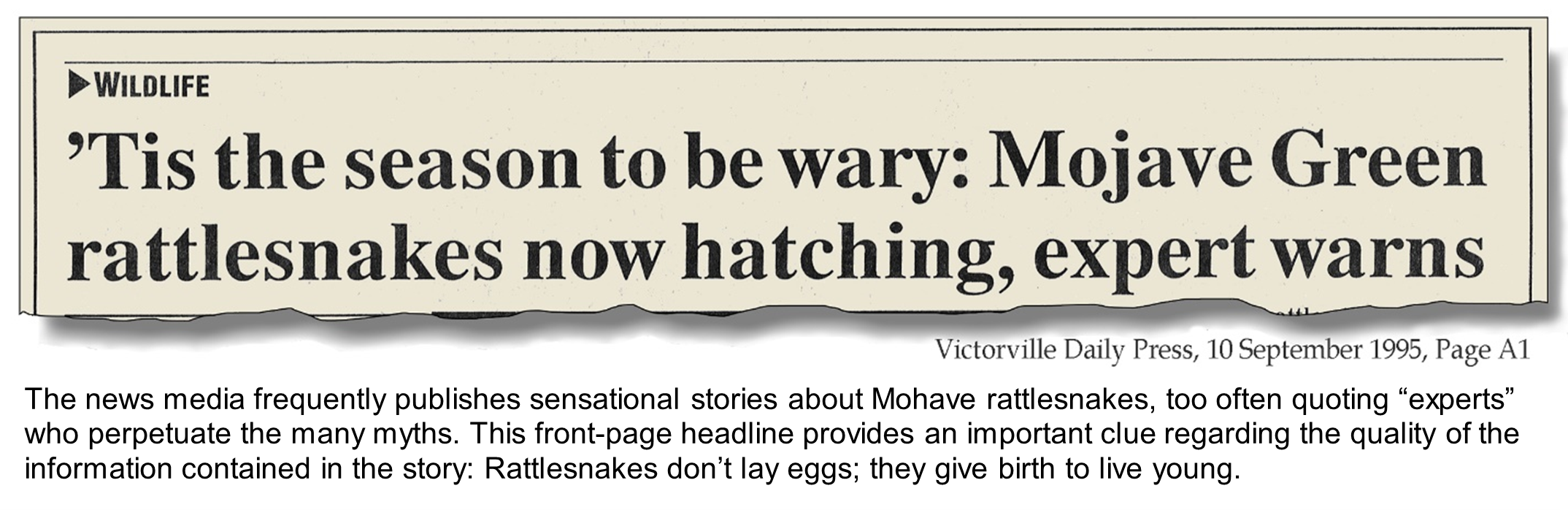

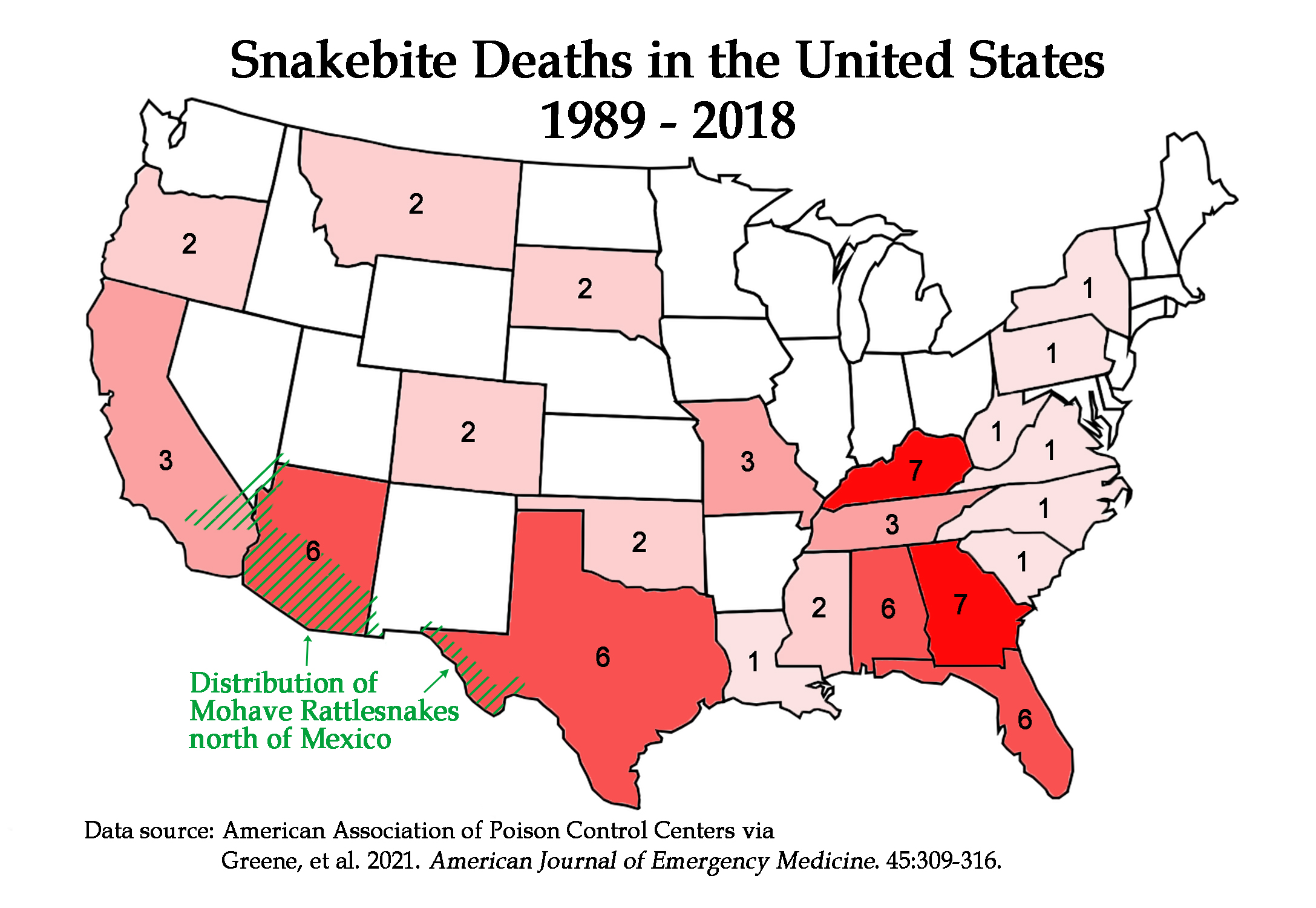

Those who study snakebite epidemiology have known for decades that snakebite fatalities in the United States are rare, with only about five or six deaths produced by around 8,000 venomous snakebites annually. North of Mexico, Mohave Rattlesnakes are abundant in the arid desert valleys from southern California, through the southwestern two-thirds of Arizona, and into the Big Bend region of Texas, in addition to small corners of Nevada, Utah, and New Mexico. Particularly in California and Arizona, Mohaves are undoubtedly responsible for many bites each year, although confirming the species responsible for individual cases is usually impossible. Yet, it has been estimated that about 30% of southern Arizona rattlesnake bites are caused by Mohaves, with proportions of bites by neurotoxic vs. non-neurotoxic Mohaves difficult to estimate. Nonetheless, CDC and AAPCC statistics indicate that most snakebite fatalities in the U.S. occur in the southeastern portion of the country, where there are no Mohave Rattlesnakes.

To be sure, Mohave Rattlesnakes can deliver a serious – even occasionally fatal – bite. And rattlesnakes, including Mohaves, sometimes produce an immediate life-threatening immunogenic reaction that produces facial swelling and airway compromise. The current consensus among physicians who treat lots of rattlesnake bites is that most first aid measures are useless, and they waste time that is best spent getting to a hospital and antivenom. In the United States, both currently available antivenoms, CroFab® and ANAVIP®, are licensed for treatment of all native pitviper bites, so specific snake identification is not necessary to choose the antidote. Problems produced by bites vary widely depending on many factors, including how much venom was injected (No, baby rattlesnakes are not worse! Venom yield increases exponentially with snake length. See clinical data here and here), size and health of the patient, and time delay to medical care. Localized tissue injury, hypotension, systemic bleeding, and acute kidney injury are just some of the problems that can occur with seriously envenomated bites.

According to Dr. Jaiva Larsen at the Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Arizona College of Medicine, and coauthor of our study, “Rattlesnake envenomated patients have many different presentations and toxic effects. Most patients can be reassured that death or the need for mechanical ventilation, while they do occur, are not common when the patient obtains appropriate advanced medical care. However, other severe health effects are also important to consider. Clinicians caring for patients with rattlesnake bites need to remain alert for a wide variety of adverse effects and should not hesitate to consult colleagues with relevant toxicology expertise – which can be done through the nationwide system of poison control centers.”