Adventurers and their dogs have teamed up to explore the wilderness for centuries. Admiral Richard Byrd brought his small fox terrier, Igloo, with him when he explored the Antarctic. Robert Limbert had his trusted camp dog at his side in the spring of 1920 when he explored the remote Craters of the Moon National Park lava fields in eastern Idaho. Unfortunately this was well before Vibram-soled dog booties, and after only three days of his planned 17-day excursion the rough lava destroyed the dog's feet. He had to carry his pup the remainder of the trip. An extra 50 pounds of pack weight must have really slowed his pace.

A well-conditioned dog is an excellent backcountry companion. Your four-legged friend can provide company at lonely times, warmth on chilly nights and protection if needed. Dogs are four-wheel-drive machines and are great at navigating difficult and unsteady terrain without the need for trekking poles. However, injury to a canine paw pad from harsh trail conditions can take its toll on their ability to complete a trip, potentially ruining yours.

Dog Feet 101

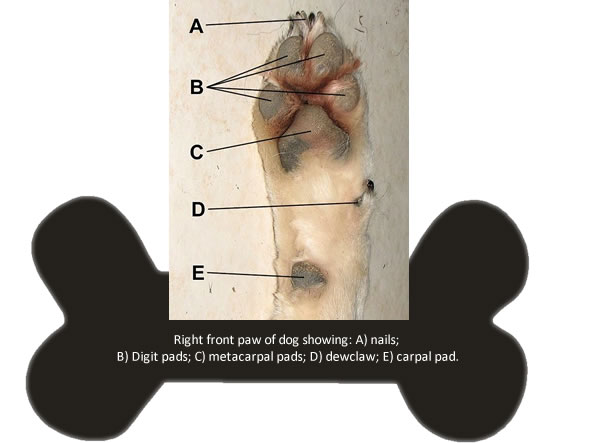

Before we touch on common paw pad injuries and how to handle them in the field, we need a brief anatomy lesson of a dog's foot. Dogs walk on their digits (fingers/toes), which are protected by thick skin referred to as the footpads. The metacarpal bones of the front feet and metatarsal bones of the back feet are raised and held at a 45-degree angle from the ground. Digit one is the vestige of a phalanx known as the dewclaw. It does not bear weight and may not be present in some dogs. Digits two through five are weight-bearing with the middle two bearing the most weight. Each weight-bearing digit and metacarpal-tarsal-phalangeal joint has an associated pad, which is tough and leathery and bears significant weight. A carpal (wrist) pad is present but not weight-bearing.

In normal gait, a dog will load 60 percent of its weight on the front limbs and mostly on the middle two digits. When evaluating paw pad injuries in the field, consider how a dog normally bears weight, as this will adjust how you respond to a particular injury. For example, while a laceration of a carpal pad will need aggressive hemostasis, since it is not a weight-bearing pad, it is unlikely to need heavy padding to allow the dog to hike home.

Paw Pad Laceration

While you are slowly trying to gain good footing and not twist an ankle in rocky terrain, your dog companion appears to be flying by you. That is until he slices a paw pad. Slick or jagged rocks are the most likely culprits. Most commonly only one paw is affected, allowing your companion to go on for awhile until you notice his off gait or the blood trail behind him.

Treatment is simple and straightforward: clean, irrigate and wrap. Don't bother trying to staple or stitch paw pads, as pad tissue will not hold stitches and staples are too painful to walk on. Apply direct pressure to control bleeding and wrap the foot as follows: layer with non-stick padding, then wrap with cast padding, cling and vet wrap (similar to Coban wrap but less elastic). The cast padding and cling layer should be tight, but the vet wrap should be unwrapped from its roll and loosely applied. Start your wrap from the toes, and if you can, leave the nails of digits two and three exposed to allow you to watch for swelling later. Continue your bandage wrap up above the carpus or tarsus to keep it from falling off. Make sure your carpal/tarsal joint is wrapped in the correct weight-bearing position. You can try to tape the top of the bandage to the fur. The bandage should be removed every 24-to-48 hours if there is significant strike through of blood or if the bandage gets wet. One very important point: wet bandages must be replaced immediately or necrosis of the underlying skin may occur. Monitor the two nails you left exposed. If the nails start to separate from each other then your bandage is too tight. Pad lacerations need rest and antibiotics. Get this dog off the trail within a day or two if possible for veterinary medical attention.

Thermal Injury

Exposed hot sand, rock or asphalt can stop a dog in its tracks. Paw pad burns are excruciating. You may first notice a problem as your dog starts "high stepping" or lifting different feet off the ground when standing still. Burned pads will necrose and slough off. Usually all four feet are affected and these dogs will need to be carried off the trail immediately. Keep the feet clean and dry. Apply a burn cream, like Silvadene, and wrap as described above with extra cast padding. Canine-appropriate medications should be provided for pain as soon as possible.

In any terrain, a tired dog may drag its feet, slowly abrading the tough pads or nails. Check your dog's feet nightly and rest him, or use booties if the pads are worn or he is prone to pad injuries. Dogs will often keep going, even when in pain. It is your responsibility to watch out for them as they are always watching out for you.

So next time you are packing up your wilderness medicine kit, include wound supplies and wraps for your favorite four-legged pal. Join me next time for treatment of torn nails and frostbite injury!