Mark Dickey, a 40-year-old experienced American caver and instructor with the United States National Cave Rescue Association (NCRC), became ill during a caving expedition inside Morca cave in Turkey on Saturday September 2nd. His group was attempting to map a new passage in the cave when he fell ill with cough, vomiting, and bloody stools.

His team contacted the European Cave Rescue Association (ECRA) for assistance, of which Mark is also a member. The next day, a team from the Hungarian Cave Rescue Service and an associated physician were able to enter the cave and reach Mark at a camp 1040m into the cave. That team was joined by the Bulgarian Cave Rescue Team with another physician and paramedic the following day. Mark receivedIV fluids, medication to protect his stomach, and clotting factors and a total of 6 units of blood as resuscitation for his gastrointestinal bleeding. Medical personnel were able to set up a “mini laboratory” to monitor his condition, according to Dr. Tulga Sener, the medical coordinator of the rescue.

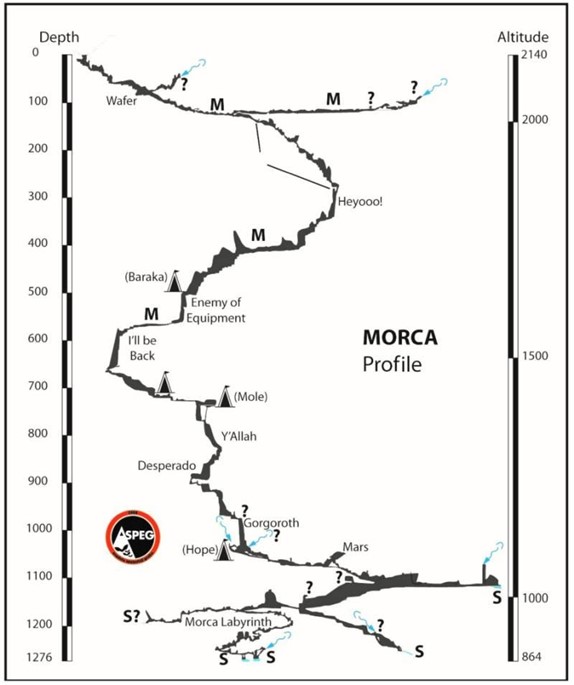

Map of the Morca cave system. Mark Dickey fell ill at Camp Hope. Source: Turkish Caving Federation

By September 7th, Mark was feeling well enough to stand and speak on camera to thank the Turkish government for activating such a rapid response. However, once stabilized, the medical team decided that the best way to evacuate him from the cave would be via a litter. A litter evacuation would take 3-4 days compared to the sixteen hours that a caver moving on their own up various rope systems would be able to do, according to Cenk Yildiz, of Turkey’s Disaster Relief Agency.

The ECRA in charge of the response divided the extrication into seven different steps, managed by six different international cave rescue teams, with over 190 rescuers involved, including doctors, paramedics, and experienced cavers. Each step included time for him to rest and for additional medical care as necessary. In addition to rigging ropes, parts of the cave had to be blasted open to widen the passages in order to accommodate the litter. A communications system was set up using Cave-Link, which can transmit data through hundreds of meters of solid rock.

Multiple camps of international cave rescuers outside Morca cave. Source: Umit Bektas/Reuters

On September 9th, the multi-stage evacuation began. Mark was loaded into a stretcher and hoisted out via a series of rigged ropes by the various cave rescue teams. The first stage of the evacuation traveled 300m from Hope camp at -1040m to -700m. The second stage on day 2 involved transport to -500m at camp Baraka. On the third day, Mark successfully passed his planned bivuouac at -300m camp “HEYOO!” to -180m. At 30 minutes past midnight on September 12th, the ECRA posted that Mark had successfully been removed from the cave and would be transported by helicopter for hospital evaluation.

Gastrointestinal illnesses are common in wilderness and travel medicine. While caves are more commonly associated with respiratory illnesses, drinking untreated water may transmit pathogens from water sources above, or other humans or animals traveling along the same cave passages. In the field, little can be done for diagnosis and treatments are limited to symptomatic relief, hydration, and possibly antibiotics, if available, pending the suspected causative organism. Dehydration is a serious risk in patients who cannot tolerate oral fluids, as well as in those who continue to lose fluids and blood in stool.

Mark Dickey is also reported to have had a significant gastrointestinal bleed (GIB) which can have a multitude of causes and multimodal treatments pending on the suspected source. Patients with signs of active bleeding and shock despite normal point-of-care hemoglobin testing should still be considered for blood transfusion, as hemoglobin testing can lag behind actual blood loss values.

Mark Dickey receiving a blood transfusion inside a tent. Source: Marton Kovacs/Hungarian Cave Rescue Service via AP

When resuscitating with blood products, current guidelines for damage control resuscitation in trauma cases recommend a ratio of 1:1:1 of units red blood cells, units of fresh frozen plasma, and units of platelets. In austere environments, whole blood transfusion is an emerging strategy for resuscitation that replicates these ratios. Whole blood transfusion utilizes pre-crossmatched blood “stored” in fellow expedition members’ bodies and does not require freezing, preservatives, or specialized transport. While it is unclear at this time if this strategy was used in the Turkish cave rescue, whole blood transfusion can be a viable option for expeditions that institute pre-expedition screening of all members’ blood types and antibodies, as well as carrying equipment and instructions for buddy transfusion, as outlined in Creating Your Own Walking Blood Bank.