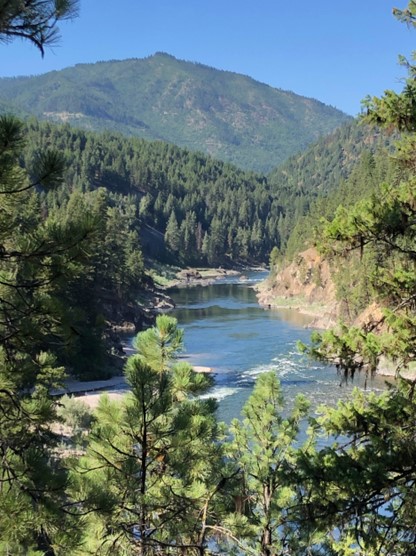

Source: Frank Zuccala

SAR team members are expected to venture into unknown terrain, often in harsh conditions, sometimes for extended periods and with limited direct support. As a result, effective training and familiarity with basic wilderness survival skills are critical for the safe and effective deployment of any search and rescue (SAR) team member. As discussed in Part 1 of this series, possession of a survival mindset is critical to enhancing the survivability of an isolated SAR team member. Without the right mentality, no amount of training or equipment will save one from the ruthlessness of nature. In addition to mindset, a systematic approach to tackling isolating events is necessary to simplify and speed decision making in the compressed time of a survival situation. There are no two survival situations that are exactly alike. However, many share commonalities. Thus, a triage-like approach helps to prioritize tasks with an understanding that situational flexibility and adaptation is critical. Part 2 of the series gave a model of prioritization with the simple, but memorable advice of “don’t die, signal your emergency, then find shelter, water, fire, and food”, and discussed the necessities of signaling, shelter, water procurement and purification. In this installation of the series, we will tackle perennially debated topics of self-rescue, firecraft, and food acquisition, then sum up the basics of wilderness survival for SAR teams.

Wilderness survival literature is largely consistent on the need for shelter, water, fire and food for survival of an isolating event. The minutiae of how to prioritize these elements of the survival strategy may vary, but most seem to agree that these are all a must. Where the true deviation seems to come in, is the idea of self-rescue when isolated. In the case of an isolated SAR team member, it is unlikely that it will go unnoticed when a team member does not check in by radio, or link up at a rally point. Hence, the signal of emergency is near-automatic and the isolated SAR team member needs only to strive to survive until located by their own team. As discussed in the first installation of this series, active signaling would be advisable to accelerate their rescue, but in most cases they should be found by their team in a relatively short period of time in ideal conditions.

Source: Frank Zuccala

In some settings, self-rescue may be a necessity. When there has been no signal of emergency or isolation -when nobody is coming- self-rescue is the only rescue likely until a notification of emergency can be delivered to the appropriate authorities. In these cases, an isolated person must decide whether or not to stay in place, or begin a self-rescue effort.

Many factors go into this decision. The health and fitness of the isolated team member, ability and certainty of navigation to a location for self-rescue, and an evaluation of survivor resources between current position and the location for self-rescue. In general, it is preferable to remain in place until rescued. This is because it is easier to conserve resources and energy, and much easier to ensure adequate shelter in one place than while moving to another.

While fire is not required to survive an isolating event, fire is a necessary tool in a wilderness survival situation as it serves multiple purposes. Fire can be used to signal for rescue, to warm a survivor, to purify water for drinking, and to prepare food for consumption. Consequently, fire making is a necessary skill to develop in SAR team members. Like any skill, the better one gets, the fewer resources one needs to accomplish the task. For example, virtually anyone could start a fire in ideal conditions with dry fuel and matches. However, add in some inclement weather and take away the matches and things get dicey very quickly.

Popular culture is replete with gee-whiz examples of how to start a fire, but the fundamentals of fire creation are the ideal place to start. Training SAR team members on how to start with identification and collection of necessary materials (i.e. tinder, kindling, and fuel) is critical. Then progress to site selection and material collection, and assembly to enhance the likelihood of ignition and sustainment of a fire with these materials. Lastly, the methods of ignition should be taught with tools ranging from matches and lighters down to various friction methods like the bow-drill.

Source: Frank Zuccala

In the photo above, students are attempting primitive fire-building with the use of the bow-drill method. While this method is arguably one of the best friction methods, it is not easy and requires great effort just to get an ember. Only when fire making is seen as a process that requires careful consideration of materials, location, and purpose does this skill become potentially lifesaving. Otherwise, it can become an unnecessary expenditure of time, effort, and calories in a survival situation in which those are not renewable resources. As with all survival skills, priorities of work based on a careful assessment of the environment, the conditions, and the likelihood of rapid recovery should dictate energy and time expenditures for the isolated SAR team member.

Fasting within a shelter to keep warm and staying hydrated with purified water is a strategy that could work for short-term isolating events. However, in addition to protection from the elements and hydration, the body of a survivor needs energy with which to perform work and heat itself. Hence, nutrition is an important element of survival strategy. The best way to ensure that survivors have adequate nutritional intake is to have an emergency ration (e.g. a Meal-Ready-to-Eat) to feed a survivor that has bivvied down and is awaiting rescue. However, due to weight and space constraints in the pack of a SAR team member, some may choose not to bring a bivvy sack. Furthermore, a ration may be expended by a longer than expected isolation. Thus, some familiarity in acquisition of food from the environment is necessary for all SAR team members.

Survival hunting, fishing, trapping, and foraging are also common topics of coverage on survival TV shows and may seem easy when viewed over 45 minutes from the couch. However, these tasks require various investments of time, effort, tools, and training to perform with any amount of expected success. Therefore, SAR team members should be trained with the equipment they intend to carry on deployment and practice their use regularly, if they hope to have any kind of success in less-than-ideal conditions - like an isolating event. Hunting is a favorite pastime of many SAR team members and others that may find themselves isolated in the wilderness. However, despite potentially vast experience with hunting, the output necessary for survival-hunting with improved tools is rarely the best use of that energy investment during a brief isolation event. Survivors must see all actions during an isolating event as an investment of time and energy. These investments must be carefully considered and constantly reassessed as the conditions change.

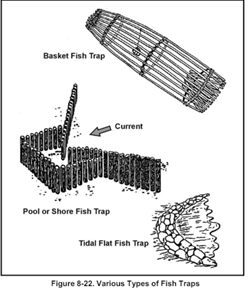

Source: US Army Survival Manual

Fishing, in its many forms, is a potentially high-yield way to acquire decent calories for relatively minimal calorie investment. With the use of fish traps, gill nets, trotlines, spear fishing, or even classic fishing with an improvised line and rod, one can potentially acquire decent calories with minimal output. Trapping and snaring similarly can help bring in nutrition without too much energy expenditure, but these skills require a fair amount of proficiency that is difficult to attain without sustained effort to acquire and maintain the skillset.

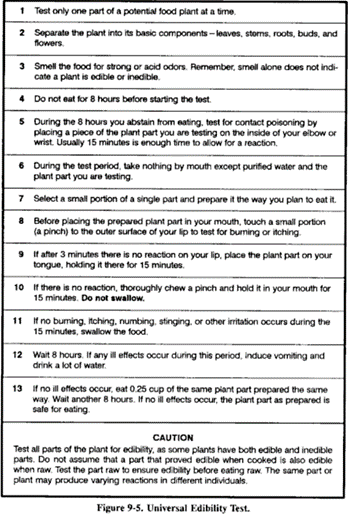

Source: US Army Survival Manual

Foraging is arguably the least expensive method of food acquisition and it takes comparatively less energy to collect huckleberries and cattails for a meal, than to chase down the nearest ungulate. It is therefore advisable to train SAR team members in the local wild edibles that they may find. Some things like dandelions, cattail roots, worms, insects and prickly pear cactus are familiar favorites of mine that are easily recognizable and safe to consume in my normal area of operations. That said, foraging too carries risk. One must be certain of the foraged items in order to safely consume them. Even then, it is prudent to perform the universal edibility test, as found in the US Army Survival Manual; a stepwise assessment of safety on plants prior to consumption. This process allows a survivor to take prudent steps toward ensuring that they are not unintentionally poisoned while consuming ostensibly wild edibles. Whatever the chosen method of food acquisition, SAR team members must be familiar with the tools, skills, indications and contraindications for each choice.

Whatever the situation, wilderness survival is a discipline, a science, and an art. It requires careful study, diligent acquisition and practice of skills, and creative flexibility. Having a systematic approach is important, but so too is improvisation, attitude, and resilience. SAR team members should take wilderness survival skills seriously. They should train and deploy with an intent to never have to use the skills, but knowing that if the worst should happen they will confidently survive the isolating event, signal their emergency, then find shelter, water, fire, and food until rescued by others or themselves.