Most visitors to the remote and enchanting blue waters of Havasu Falls in northern Arizona don’t imagine their journey ending with a medical evacuation out of the canyon, but that’s just what happened recently to countless guests. Last week media coverage reported the spread of a “mystery” gastrointestinal illness impacting hundreds of hikers per social media reports. Starting on June 8th, hikers in the area started to present with symptoms of fatigue, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea with some experiencing severe illness and becoming unable to hike the 10 miles back out of the canyon and needing airlift evacuation.

Havasu Falls (thecanyon.com)

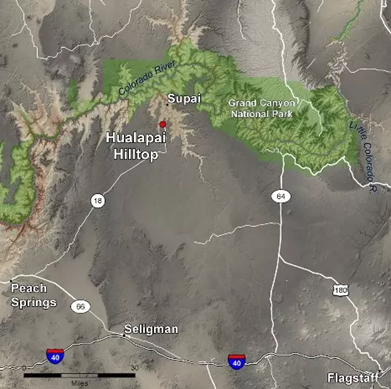

Havasu Falls is located on the Havasupai Indian Reservation in northern Arizona, adjacent to the Grand Canyon National Park. Havasupai means People of the Blue-Green Waters which are the major attraction, and economic force, of the reservation with thousands of visitors making their way on foot to the remote and roadless village of Supai and the subsequent falls. Reservations through the tribe are required to make the 8-mile hike from Hualapai Hilltop, where visitors leave their cars and start down the Havasu Canyon to the Supai Village, then another 2 miles to the Havasupai campground where most hikers spend their time. The large but typically crowded 200+ capacity campground includes composting toilets and a potable water source, Fern Springs, which is tested for potability bi-weekly. This source was deemed safe for consumption on June 6th.

Havasupai Vicinity Map (nps.gov)

The Havasupai Tribe in conjunction with the Indian Health Services, Coconino County Health Department, and Arizona State Health Department released a public health statement covering the incident on June 14th. It stressed that this outbreak could be part of a larger occurrence across the northern Arizona region and the priority of preventing further spread to hikers and local tribal members. The tribe in conjunction with the IHS are tracking new cases. The tribe is taking steps for additional cleaning and disinfecting in the campground as well as a new water station. The IHS medical clinic in Supai is available to treat any visitors experiencing GI symptoms. The tribe reminded visitors to “(i) take responsibility for their personal hygiene while visiting and (ii) properly dispose of personal trash by hauling it out. The composting toilets are not for your personal trash”. While no official statement of the cause of this outbreak has been released, a health advisory put out by the IHS is indicating the illness is likely viral in nature.

While this GI illness may still remain a mystery, there is a likely culprit: Norovirus. Noroviruses are non-enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA viruses with genogroups I and II responsible for human cases of the “stomach bug”. Norovirus is widespread and according to the CDC is the most common case of gastrointestinal illness in the US with approximately 21 million cases and 2,500 outbreaks annually. The virus is spread quickly through contaminated food, water, air particles through vomiting and stays on surfaces with person-to-person transmission being most common. The inoculation period is less than 1.5 days with the illness typically self-resolving within 1 to 5 days, however the virus can shed in stools for up to 60 days. Common symptoms include nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain and cramping, diarrhea, myalgias, headache, and chills. Typically cases can be treated with oral rehydration and slow return to normal intake. Severe illness primarily results in significant dehydration and electrolyte deficiencies requiring hospitalization and treatment with IV hydration, anti-motility, and anti-emetic agents may be needed. Diagnostic confirmation isn’t typically used for routine cases but enzyme immunoassays and RT-PCR are used to confirm infection during outbreaks. Proper hand hygiene with soap and water is the best way to prevent spread of the virus as there is no vaccine currently available.

Norovirus outbreaks typically occur in confined spaces – cruise ships, health care facilities, childcare centers – but this isn’t the first time a potential outbreak has occurred in the wilderness or outdoor setting. Recent outbreaks include a 2022 event on the Pacific Crest Trail, concern for spread on the southern Appalachian Trail in 2024, and even occurred upstream of Havasupai in the Grand Canyon National Park in 2022. Research from the Grand Canyon outbreak in rafters and backpackers found that interactions with ill persons and use of only hand sanitizer or water (but not soap and water) during the trips results in increased risk of transmission and subsequent illness. Recommended mitigation strategies from this study include “symptom screening before the trip starts, prompt separation of ill and well passengers, strict adherence to hand hygiene with soap and water, minimizing social interactions among rafting groups, and widespread outbreak notices and education to all park users.” All strategies that could be implemented for any wilderness outing.

This research falls in line with general guidance from the CDC and National Park Service in preventing and responding to norovirus in the outdoor setting. With the takeaways being:

- Wash your hands carefully with soap and water, especially after using the toilet, changing a diaper, and before eating, preparing, or handling food. Alcohol-based sanitizers are less effective against norovirus.

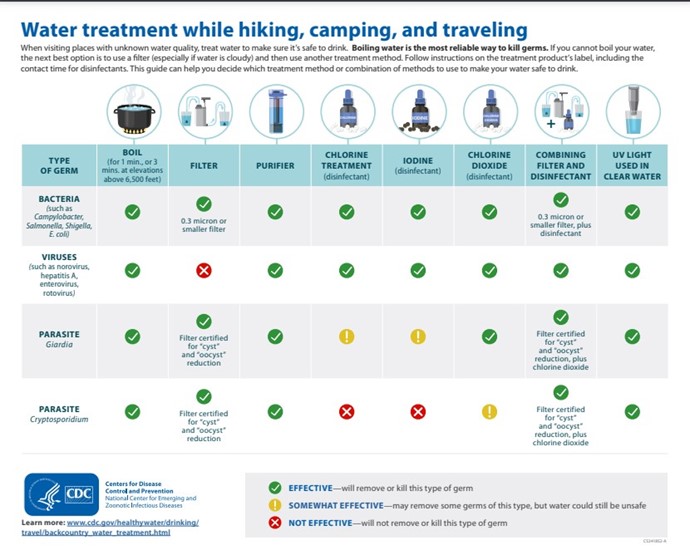

- In the backcountry, boil your water or use a chemical disinfectant; most filters are not sufficient to remove norovirus.

- When preparing foods, wash fruits and vegetables well and cook seafood thoroughly.

- Clean and disinfect surfaces, counters, and utensils regularly with a chloride-bleach solution.

- Isolate sick participants as much as possible.

Outbreaks such as this one at Havasupai highlight the importance of prevention and proper hygiene when venturing out into the wilderness. In addition to prevention against viral gastrointestinal illness, taking the proper precautions against all waterborne illnesses including bacteria and parasite etiologies through proper water treatment is paramount to having a safe adventure. The recently updated 2024 WMS Clinical Practice Guidelines on Water Treatment for Wilderness, International, and Austere Situations recommends treating water in wilderness areas with nearby agricultural use, animal grazing, or upstream human activity. Various methods of water treatments and effectiveness against pathogens are outlined in the CDC graphic below.

CDC Water Treatment Diagram (CDC, cdc.gov)