Around 8PM on Friday, October 27, an unnamed male climber became stuck with his leg lodged into Indian Creek’s Generic Crack for 12 hours.

The climber slipped while 100 feet up the climbing route, lodging his knee into the crack. At the time, partners with the climber retrieved soap from their nearby van, dousing the climber’s leg in an attempt to free it. However, the climber was wearing pants, and the soap did little to help. They subsequently tried motor oil and medical lubricant, none of which worked to dislodge the climber’s leg.

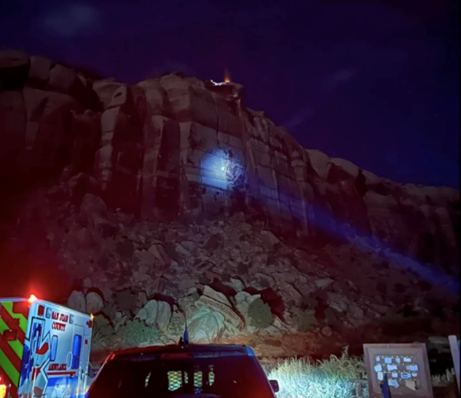

San Juan County Search and Rescue was called to the scene first. After several hours and multiple attempts to free the climber, the Grand County Search and Rescue team was called in to offer “more man power.” Rescuers were flown by helicopter to the cliff’s edge before rappelling down to the climber. In an effort to relax the climber’s leg muscles before hoisting him out, a paramedic administered ketamine. Using a seven-to-one hoist system, the team was subsequently able to pull the climber from the crack.

Grand County Search and Rescue team preparing to free the stuck climber. Source: Fox News

Grand County Search and Rescue Team attempting to free the stuck climber. Source: Climbing.com

The climber suffered only minor injuries despite the situation lasting a full 12 hours. The San Juan County Search and Rescue commander, Avery Olsen, suspected soap would have worked in this situation had the climber been wearing shorts. In this case, administering ketamine prior to dislodging the climber likely sufficed not only to relax the climber’s muscle but to control pain and anxiety as well.

Research shows that failure to adequately manage pain may elicit a significant stress response and increase patients’ risk of developing posttraumatic stress disorder. In addition, the longer a patient’s pain remains uncontrolled, the more likely they are to become increasingly sensitive to painful stimuli and develop even more difficult-to-control pain. This paradigm is a particular challenge in austere environments where medical personnel and supplies are limited.

In 2014, the Wilderness Medical Society published guidelines for the treatment of acute pain in remote environments. The guidelines outline several qualities that make a medication ideal for wilderness use. These include medications that are compact and lightweight, durable, nonsedating, wide spectrum of use, biochemically and environmentally stable, multiple routes of administration, and minimal side effects.

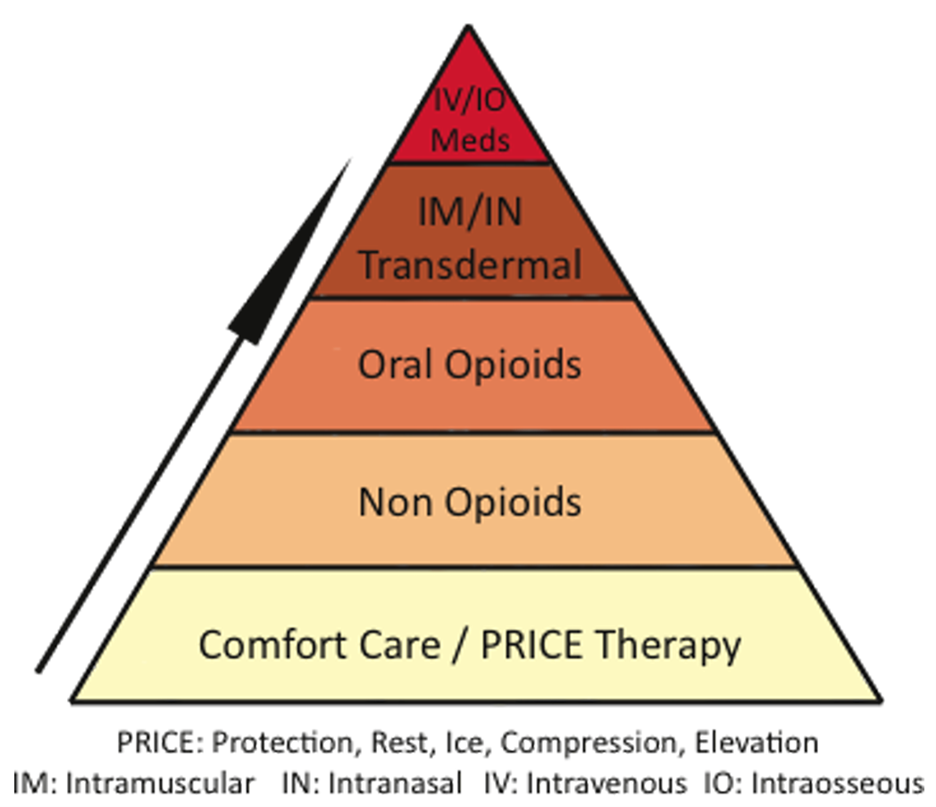

The guidelines themselves are introduced in the form of a pyramid of escalating analgesic care, beginning with the safest and most accessible interventions. The pyramid reflects how invasive or stronger means of analgesia are suggested only for patients in extreme pain after safer, less-invasive options have been considered.

Pain Pyramid. Source: WMS Acute Pain Practice Guidelines

On the use of ketamine, the anesthetic administered to the trapped Indian Creek climber, the Wilderness Medical Society guidelines suggest, “It can be used alone at higher dissociative doses for moderate to deep sedation during painful procedures… Patients are usually amnestic after the event, which is beneficial if a prolonged evacuation ensues.” Other useful applications cited include painful procedures of short duration such as fracture reduction, wound repair, and amputation. However, the Wilderness Medical Society emphasizes that attention to the airway be maintained as there is a risk of laryngospasm along with increased heart rate, blood pressure, and salivation. This was the drug of choice for the Thai cave rescue in 2018.

In addition to pharmacologic management, the Wilderness Medical Society guidelines highlight the use of comfort care in wilderness medicine. Simply using a patient’s name, reviewing the plan for pain management, and approaching the situation with empathy can make all the difference. Research has shown that these interventions can both reduce patient-reported pain and lower heart rate responses to pain.

Reviewing the Wilderness Medical Society guidelines when planning trips to remote areas may better prepare travelers to treat those suffering from pain. The well-prepared rescuer will consider bringing along multiple modalities to treat pain based on the potential mechanisms of injury related to the excursion as well as evacuation times.