An electric buzz...

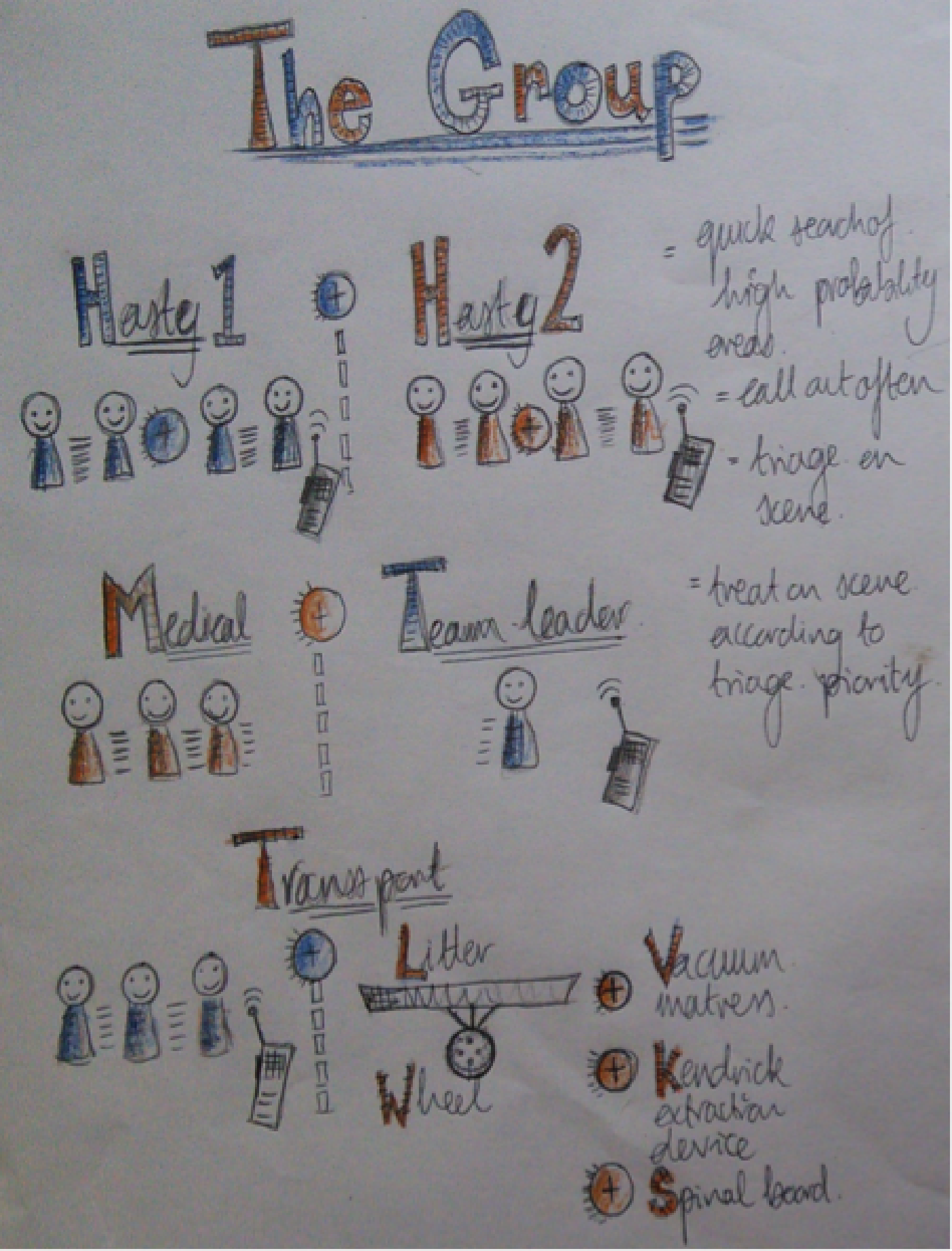

filled the wooden, log-fuelled cabin. Plates scraped clean and stomachs full of dinner, chatter burst from lips and fingertips flexed. We waited with impatient faces, booted feet, and packed bags. Clock watchers and weather checkers, we steadied our legs for news. We had two groups – A and B – and four teams with them: Hasty 1 and 2, a medical team, and transport. Our group leader furrowed his brow, clipped and unclipped his backpack, untied and tied his shoelaces, and triple checked with all of us, “Who’s not ready? Are you ready? Everyone happy with your roles?”

"READY,"

came the reply, or as ready as we could be for the exercise we had been warned could last as long as 2 a.m. The exercise included search and rescue (SAR), triage, treatment, and extraction of patients using the protocols, and technical and improvisational skills we had learned over four days of intense training. This was the final test.

The briefs for each team came in, filtered down though our group leader: There had been a plane crash in the woods in a south-easterly direction from our current location. This was a mass casualty incident (MCI). The Hasty team set out first. Not knowing the number of casualties or exact location, our feet followed the compass point, further and further away from the glow of the cabin. Head torches cut through the dark, crisp evening and the fog of our breath. Our voices burst through the trees, bouncing from branches and through leaves, “Hello!”

With our ears cupped by hand, we listened for a rustle hidden by the wind, a whisper of a reply. Our boots continued to tread the dirt path through the eerie silence, crunching gravel and compressing lose dirt to mud, avoiding puddles graced by ice. We climbed, calves tight and thighs burning, the hill twisting out of sight. We checked-in through the radio static, updating our progress every 15 minutes, employing headcounts and buddy systems, ensuring the safety of the team.

Stop, shout, seek, flash, flash, continue, repeat. Progress was slow but missing a clue could be vital. We had been taught to look for objects out of the ordinary like track marks, to shine our lights, and observe between trees and foliage, focusing on the “empty” rather than what our eyes were naturally drawn to. Expand your vision, move your body, look behind you, and scan your eyes through the darkness, all the way to the tops of trees with complete awareness of the surroundings. Two false leads pushed themselves to our attention:

1) A small hut with shining, inviting windows and shadows of life.

2) A loose orange ribbon, flapping against the girth of a tree

“Hello,” we persisted, projecting our words through cold, pursed lips. Nothing. Again we tried – still nothing. Our feet slid over slick ground, onward eyes and ears intent on finding signs of life.

A fellow student shouted, “Look!” She almost couldn’t contain her excitement, picking up her pace, scrambling through the undergrowth. Faint flames of a fire and a dim, desperate flashlight shone through space-hungry branches. “Hello,” united through our voices. Strides synchronised, we ducked and traversed trees felled by the brutality of the previous night’s storm. The wind creamed our words to soft inaudible sounds but it carried a feeble reply, “HELP US! Over here!”

Our hearts leapt to life, lungs pumped air, eyes focussed, and balance stabilised, honing in on the sound of human voices. Sweeping with torches and stray stones dislodged by the soles of our shoes, we stumbled on a desperate sight – five bodies, one standing and four on the floor. A woman, hunched over the small smouldering of twigs, cried out, her voice mixed with pain, skin cold, shrouded by dirt that clumped in fingernails and hair. She was crying, which meant her airway was patient. However, the same couldn’t be said for the three still bodies lying undisturbed by our entrance.

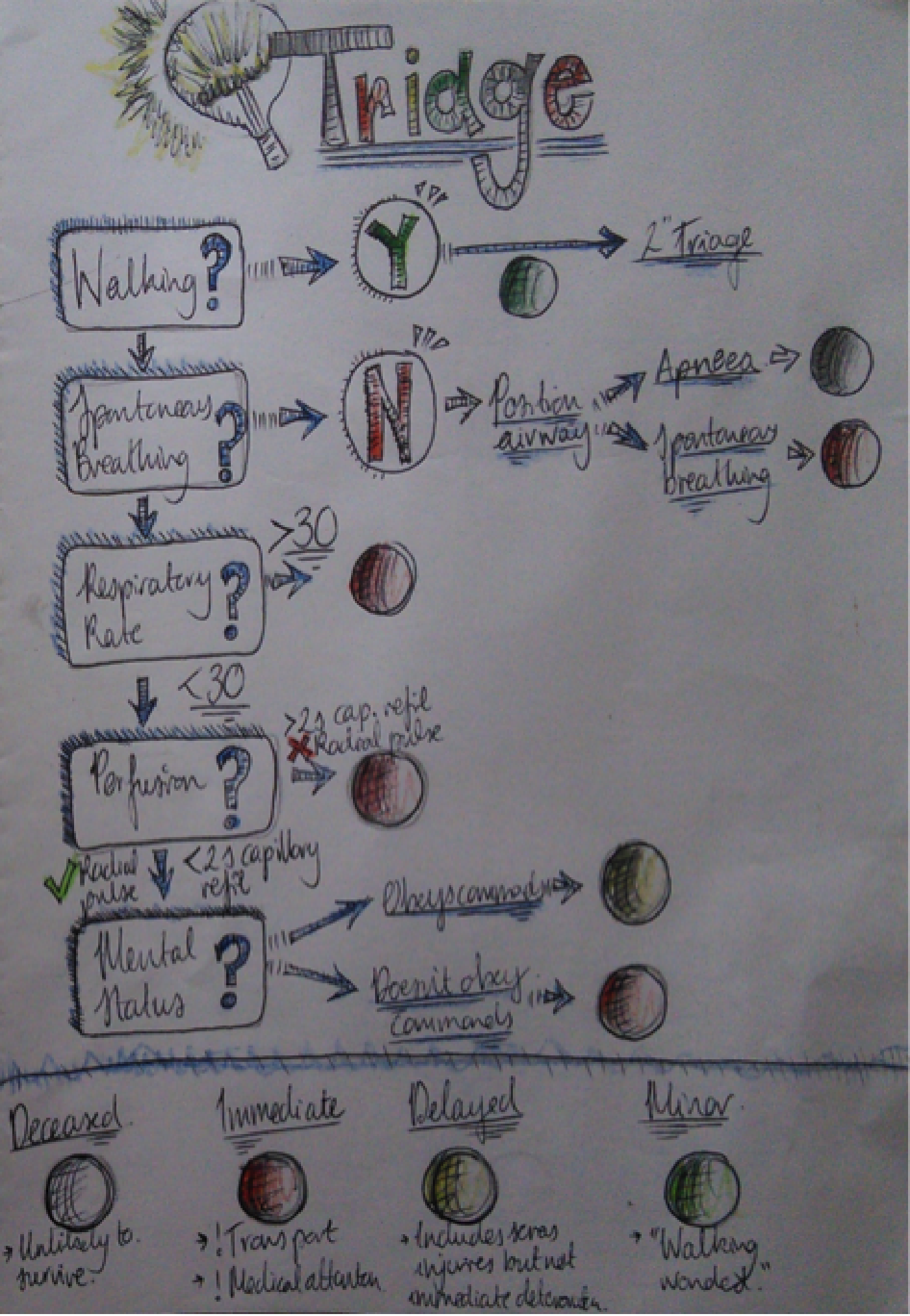

One of Hasty teams had marked our exit from the path with a glow stick to ensure the swift arrival of both our medical and transport teams. We radioed through, updating the number of casualties and our location, ensuring communication did not delay us from the task at hand. In triage we had to detach ourselves from the humanity of the situation, which in the end is how to have humanity in an MCI. Our job was to identify patients in need of critical medical assistance, which meant ignoring cries and screams for help, transferring our attention to those with lower levels of consciousness. We were robots, churning through the written manuscript. Within 30 seconds, a casualty was processed, marked by colored tape, and we moved on, literally handing them their fate but a strategy to save the most people. You are naturally drawn to the ones that scream, cry, and weep, but those are the ones that are safe. They have the ABC’s: Airway, Breathing, and Circulation (or check for Catastrophic haemorrhage). You have to draw a block over your ears and focus – airway, breathing, circulation – then stop, tag, and remind yourself that treatment is not your job.

The casualty I came to was a baby. Demonstrating no signs of life, I listened for sounds of breath while at the same time feeling a pulse, willing my ear to pick up on the slightest noise. I gave five rescue breaths and reassessed. Nothing. I felt compelled to start CPR, my focus slipped, the desire to help winked at my sympathy and reeled me in, but I needed to stick to the protocol. I shouted for tape, “BLACK!” Turning my back to continue my assigned task, I walked away. One Hasty team stayed as the medical team arrived through the thicket, their headlamps a hope that we were not just abandoning those we had marked. We set off again, Hasty 1 with new priorities:

1) To ensure we had not missed any casualties.

2) To assist our struggling transport team over the tough terrain, as we would need a total team of six to transport a litter with a patient.

We called out again, back into our initial routine, and came to the end of a rough path meeting the main trail. Marking the trail merge with yellow tape, we buzzed our communication through the radio; rough, like sandpaper, we received a relay. Skittering down the trail, more treacherous than our uphill stretch, our heels slipped on frost and slick gravel. Our breath jittered in our chest; fingers felt the edge of the cold as it skimmed over the tips.

We found our transport team with their chests puffed, arms straining, and layers unzipped, braced against the slope, their weight pressed on the wheel which had become flat over the course of their journey. The same wheel we were all relying on to transport our patients to definitive care. We grabbed onto the sides of the plastic litter and suddenly we became part of a rescue operation. With the transformation of “subjects” to “patients,” it felt less like a cutthroat procedure. We had regained the human element in our mission. The once cumbersome, impossible load flew over the upward climb. We peaked at the top, and with a sigh of relief from our Achilles tendons we pinched a left onto our marked path. The leaves and branches met our faces with the same force as the tough decisions that followed. Two “Red” patients, two “Green,” one “Black.” So which of the “Red” patients should be transported first?

Patient 1

-Evisceration Injury

-Head trauma with + Airway

-Heart rate 120

-Altered Mental Status

Patient 2

-Open femur fracture reduced

-+ hemostasis

-Heart rate 100

-Normal mental status

Our team leader made the final call and we transported Patient 1 first. Patient 2’s condition had been stabilised by the medical team; however, Patient 1 had a possible head injury and altered consciousness, and so their condition was time-critical. Already secured on the spinal board, we lifted the patient onto the litter with extra layers to prevent as much heat loss as possible. The two patients who had been triaged “Green” walked alongside our team.

The journey back was slow. The terrain and the friction on our hands meant frequent stops. In addition, transporting an unstable patient is like balancing an elephant on a fine thread. We frequently checked A, B, C’s, transporting the patient feet-down as much as possible. We worried about asphyxiation because we had no airway devices and, being strapped on his back inside the litter, the only intervention we had was a basic jaw thrust. Time tiptoed slowly alongside us, and with aches in our shoulders and backs we arrived back at base. After what seemed like hours, its tendrils of comfort teased us, as we knew that following our handover it was a quick turnaround to face the transport of another critically ill patient under far from ideal conditions. Who knew what help B team would require once our final extraction was complete.

Night scenario debrief.

The night scenario is the culmination of the WMS Elective Wilderness First Responder (WFR) course – provided by Roane State Community College – and an opportunity to employ and improvise on all skills learned over the last week. Over the course of several hours, not before many moments of fear, frustration, self doubt and near-hopelessness, our students gain team building skills, leadership skills, confidence, heart, and pride. The experience teaches medical students about what their patients and pre-hospital teams go through prior to arriving at definitive care, where most physicians meet their patients for the first time. As it turns out, what happens before the hospital is of vital importance.

The group on the final night of the elective.

The WMS Student Elective in Wilderness and Environmental Medicine happens every February in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. It is open to senior medical students. An inaugural second block of the elective will occur in April 2018 in Breckenridge, CO.