As I prepared to climb Mount Aconcagua with my brother, my emergency medicine tuned brain couldn't help but dream up the thousand various ways in which I could find myself on the opposite side of the doctor-patient relationship. Mount Aconcagua is the tallest mountain in the world outside the Himalayas and the second tallest of the classic “seven summits.” It is a part of the Andes Mountain Range in the Mendoza region of Argentina, soaring to a height of 6,962 meters. Climbing Aconcagua, though not considered a technical climb, has many challenges: exposure, altitude, extreme cold, lack of resources, and isolation, to name a few. Preparation is key.

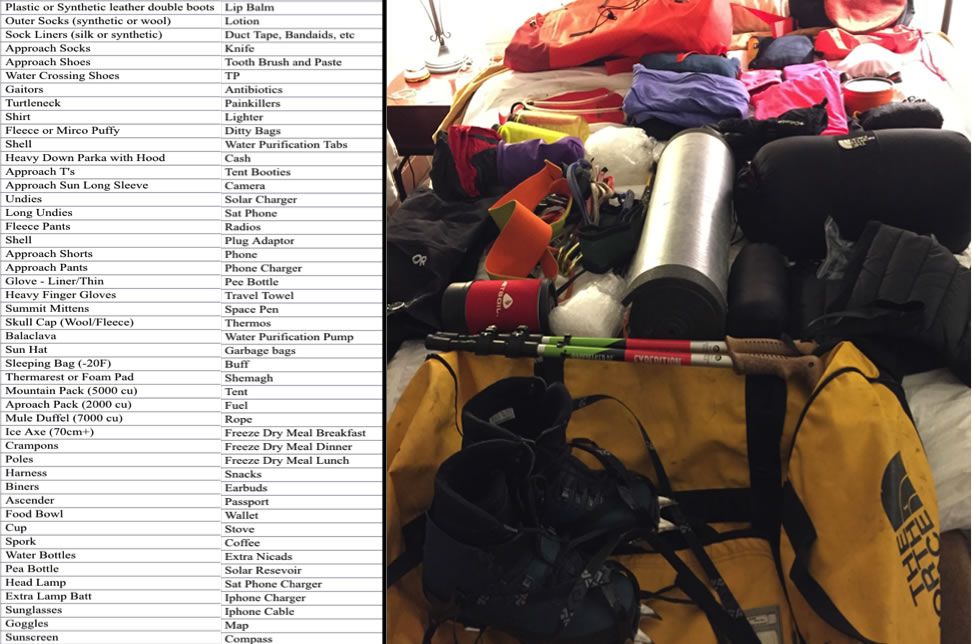

There are innumerable packing lists available online that tend to emphasize both warm and light weight gear. There is no greater contradiction. I have never spent so much money before even departing for a trip. However, cold related injuries can be devastating and these were not the type of souvenirs we hoped to bring home. Thus the credit card continued to swipe and the gear pile continued to grow to daunting levels.

Figure 1: Author’s gear list and staging.

Most hikers hire a mule service to carry a majority of the summit gear that isn’t necessary at lower elevations to meet you at the base camp. Considering I could hardly drag the packed bag across my apartment, hauling it up a mountain was hardly in my realm of capabilities. So this was fortunate. While I wanted to count this packing process as “training,” I was told this may leave me ill-prepared for the rigors of the hike.

Figure 2: Pack mules headed to base camp.

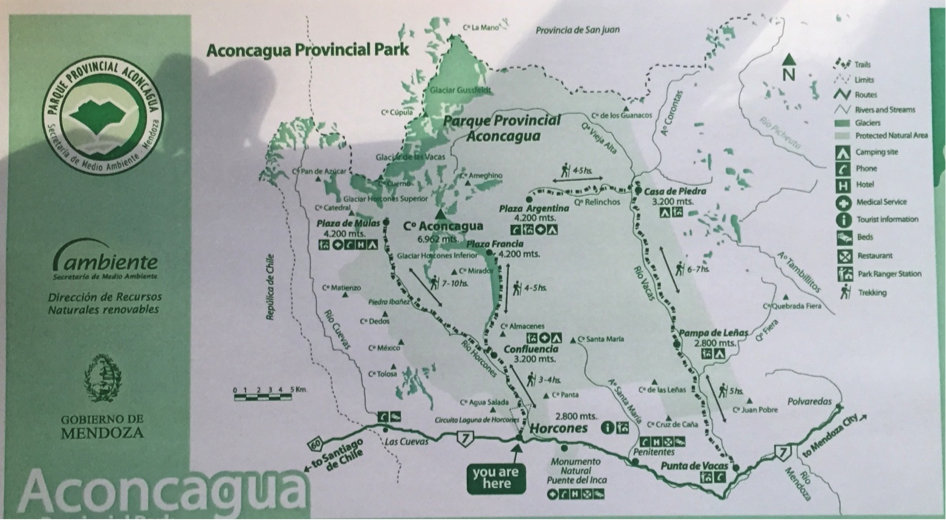

I focused on cardiovascular training in the months leading up to the hike, mainly in the form of running and stair climbing with my weighted pack. We planned to climb the mountain within a week, but gave ourselves a two-week window to account for bad weather or acclimatization issues. This meant gaining and losing 4,012 meters and traversing 161 kilometers in one week. No problem, right? Not surprisingly, this military style plan was decided on entirely by my ultramarathon-running brother.

Figure 3: Aconcagua route map provided by the permit office in Mendoza, Argentina.

Even though I felt I was in good shape, training at sea level will never completely prepare you for the added effects of altitude. Acute mountain sickness (AMS) is the most commonly cited reason for the low success rate of this mountain. About 3,500 people attempt the hike yearly with only about 40 percent reaching the summit.

It requires a great deal of self awareness to notice the effects of early AMS and know when pushing on could be dangerous. Luckily, the park permit fees do support some safety checks to account for summit hopefuls’ varying levels of said awareness. There is a medical screening exam at the base camp and those who fail this exam are not allowed to continue to the summit. The medical personnel have a set acceptable range for both blood pressure and oxygen saturation. Having this evaluated was my first personal experience of the anxiety that some people experience with visiting a physician. I couldn’t help but worry that “white coat hypertension” could keep me from my goal. Many, however, after passing this screening still go on to suffer serious effects of altitude. There have been reports of both HACE and HAPE cases on Aconcagua. While preparing for our summit attempt, we witnessed a helicopter evacuation of one such case.

<iframe src="https://player.vimeo.com/video/165622570?h=90e3a58de4" width="640" height="360" frameborder="0" allow="autoplay; fullscreen; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

<p><a href="https://vimeo.com/165622570">Helicopter Evacuation from Plaza de Mulas base camp.</a> from <a href="https://vimeo.com/user51921879">Wilderness Medicine Magazine</a> on <a href="https://vimeo.com">Vimeo</a>.</p>

Figure 4: Helicopter evacuation video from Plaza de Mulas base camp.

While AMS is one of the most commonly discussed and studied illnesses of high altitude that can be found in the literature, I can tell you with no scientific certainty that gastrointestinal distress is by far the most common topic discussed amongst hikers on Aconcagua. Meeting strangers abroad is one of my favorite things about traveling. Each location leads to very unique small talk. Having socialized with groups of doctors in the past, I am no stranger to typically taboo topics being brought up over a cocktail. Someone bringing up a case about being impaled by objects, festering wounds, that particular smell of clostridium difficile diarrhea, or chlamydia is not a rare occurrence in my social life. However, while eating dinner in a tent on Aconcagua, it seems no description of bodily functions was off limits. Consistency, color, and frequency were just a few details I was privy to. Of note, at any camp above Plaza de Mulas base camp, any solid or semi-solid excrement must be deposited into one’s own “receptacle” (a not sturdy enough plastic bag) and carried both up and down the summit to be returned to officials when arriving back at base camp. I had the unique opportunity to be scrutinized by officials on my return from the summit questioning the quantity of stool I had produced. They alleged that I may have committed an illegal dumping on the summit. This is a kind of judgment I never in my life could have guessed I’d experience. Nonetheless, without “evidence” of my alleged act, the officials had no choice but to accept my excrement bag and allow me to leave.