I enjoy foraging food from wild plants as I hike. It is a great feeling to snack as I walk, add a bunch of greens to my sandwich at lunch or add some wild berries to my pancakes or cereal.

When wild foods are available, what I gather is primarily supplementary to what I carry in with me. The kinds and quantity of foods I pack-in depends on what I predict I will find along the way. Unless I am taking on a challenge, I want the gathering part to be fun and a bonus to the experience of hiking, not lots of work or drudgery.

Gathering and eating wild foods along a trail is like child's play: a five year old can do it. Yet as Groucho Marx, a comedian actor of the 1930s, once said, "Go find me a five year old, I can't make heads or tails of it!" Yes, a five-year-old Native American child of long ago could easily identify and know what to do with plants found along a trail. That is because her parents, through daily living and example, taught her everything she needed to know from birth.

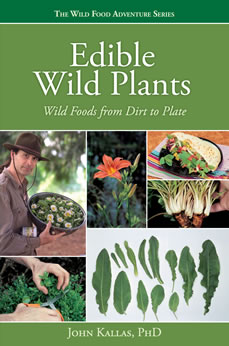

Photos courtesy of John Kallas, all rights reserved

1. Butternut (Juglans cinerea): Produces walnut-like nuts in very hard shells encased in a green husk. Grows in the northeastern states from Michigan to Tennessee. Found in mixed deciduous forests from sea level to 1,000 feet in northern states and up to 5,000 feet in its southern range. Photo courtesy of John Kallas. All rights reserved.

2. Glacial Lily (Erythronium grandiflorum): Leaves, flowers and underground corms are edible. Found in the west along the coast mountain ranges, the Cascades and the Rockies. Altitude ranges from 3,500 to 6,500 feet. Photo courtesy of John Kallas. All rights reserved.

3. Ramps (Allium tricoccum): Produces edible leaves and small onion like bulbs for spring harvesting. Found in moist woods in the eastern half of the US. Grows from sea level to 1,000 feet in Michigan, but at higher elevations (up to 4,000 feet) in the southern-most states. Photo courtesy of John Kallas. All rights reserved.

4. Groundnut (Apios Americana): Produces edible underground tubers all year. Found in moist woods and occasionally submerged wetlands throughout the eastern half of the US. Grows from sea level to over 1,000 feet, occasionally higher in the south. Photo courtesy of John Kallas. All rights reserved.

Most people today know nothing about plants and even less about what is exactly "edible" on many plants. What they do know is that modern life is about instant gratification. Want to buy something? Whip out your credit card. Want to know something? Look it up on your Internet browser. Want to eat something? Go to a drive through. This tends to produce the misconception that all one needs is a simple list of edible plants to eat well along the trail. As a professional wild food educator, I have great concern about this thinking because superficial knowledge is not enough. Successfully identifying, eating and enjoying wild foods along a trail depends on the following important concepts.

How Well Do You Know Plants?

If you can already correctly identify the plants found along the trail you will be traversing, then you are well on your way to going the next step to learn their food potential. If you do not know plants, then your journey will be a longer one. Even with the best identification resources, there is still a learning curve.

Knowing wild foods, however, is more than just knowing a plant is edible. You must know which parts are edible, at what stage of growth and how to prepare them. Some plants have multiple attributes. That is, one part may be edible, another poisonous, another medicinal. So it is not like going into the grocery store where you can be totally ignorant and still find food. In the wild you are responsible for making what may be life-determining decisions about exactly what you are going to consume.

Where Are You?

If you are only interested in hiking a trail, any beautiful trail will do the trick. However, if you are interested on using the food resources of that trail, where you are makes all the difference in the world. The plants are different in the forests of the Pacific Northwest then the forests of Maine. Further, the plants of a forest trail are different than those of a savanna or bog filled area. So you need to know the specific edible plants of your region and the biomes you will be passing through.

What is Your Elevation?

Trails can be at sea level but they can also be at 5,000 feet. Different elevations dictate different species. Learn the plants appropriate for the elevation you will be hiking. Want specific wild foods? Hike at the elevation where they thrive. Higher elevations mean harsher conditions, which means only the hardiest of species survive. Want more variety in your wild foods? Hike below 2,000 feet.

What Time of Year Is It?

Plants are seasonal as well as their edible parts. If you want to feast on nuts, hike in the fall. If you want greens, hike in the spring. Fruits are mostly in the summer. Winter is barren for the most part. The seasons in New York are very different from the ones in the gulf coast or in the Rockies.

If you are going to hike a trail, knowing its biome and region, what's available at the season and elevation of your visit will reveal the foods you can expect to find. You should not expect to get full meals or complete nutrition from trail foraging since the aforementioned issues limit what is available. That is why you should always pack-in plenty of food and enjoy the creative practice of supplementing with wild foods that you find.

Finding a Good Teacher

You may be thinking by now, "How could I possibly learn all this?" While this may seem daunting, it is amazingly easy if you find the right teacher, get some good books and engage in some dirt time. The knowledge is not difficult. It's access to it that is sometimes the challenge.

The best way to learn about wild foods is to find a good teacher for hands-on training. Like any other commodity you need to search for who is available in the region you are going to be foraging in. Since there are not many wild food instructors in North America, you may not have much choice or any instructor at all. Eat the Weeds is a good website to link to possible wild food instructors in your area. Don't stop there because not all instructors are listed. Investigate your local area. If possible, ask at a county extension office or a university biology department.

Other options are to join local plant groups and take wild plant hikes. They may not be focused on wild foods but you will start learning plants. It is helpful to attend regional wild food weekends and rendezvous. They typically happen from April through September and feature one or more instructors. They are reasonably priced and take some travel, but are well worth the effort. Wild Food Adventures provides information and links to major wild food events in North America.

Finding the Right Book

Since plants are regional (except edible weeds), books you acquire should be specific to the region you want to forage. Search using the key phrases: "edible wild plants of," "wild flowers of," "plant identification of," and insert locations. Start with specific locations and get more general if you are not successful at first. For example, search for "edible wild plants of Oxbow Park", then of Oregon, then of the Pacific Northwest and finally of the Western United States. Of course plant identification guides will not teach you about edibility but identification is an important foundation for learning edibility.

Not all books are equal in quality, though you may not have a choice in your particular area. The best way to determine if the author knows their stuff is to establish that they clearly have personal experience with each plant described. If they do, there will be a lot of personal references in the explanations instead of general statements. Authors with experience will also provide lots of detail about edible parts, optimal stage of growth for harvesting and clear processing directions if processing is necessary. The best books have clear sharp photographs that reveal important plant features. Many books, unfortunately, use amateur snapshots that show no useful detail. Look for the good stuff.

Get Some Dirt Time

Learning is developmental and accumulative, and there are many plants to know. Experiment along the trail with plants you've learned and then learn some more. Never experiment with unknown plants, only experiment with plants you've learned well and know to have edible parts. After a while, foraging will seem effortless and be nothing but fun. Pull up a log, stoke the fire, fry up some wild huckleberry pancakes and pass the syrup.