The Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) is well-known by its tagline: “the charity that saves lives at sea.” It operates a search-and-rescue service around the coasts of the United Kingdom and Ireland. The RNLI has four main facets to its service: lifeboats, lifeguards, flood rescue and coastal safety education.

Founded in 1824, the RNLI has constantly adapted to ensure it stays at the forefront of lifesaving. Two recent examples include the introduction of the RNLI’s ”Big Sick, Little Sick” approach to casualty care and the expansion of its international work.

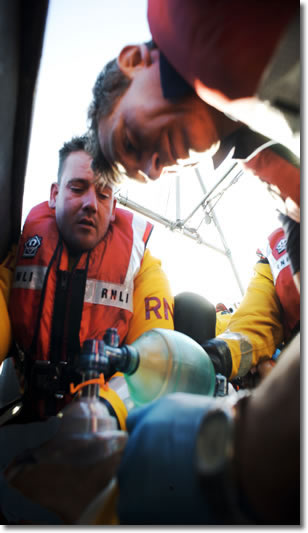

Two RNLI crew members carrying out a casualty care exercise. Photo by Nigel Millard.

Big Sick, Little Sick

As only one in 10 RNLI volunteer lifeboat crew members has a professional maritime occupation, the charity provides rigorous training - including casualty care - which takes place either at the charity’s specialist training facility (the RNLI College) or at their local station.

Paul Savage, the RNLI’s Clinical Lead, developed a casualty care course, colloquially known as “Big Sick, Little Sick,” to simplify the approach to casualty care. The course is designed to ensure casualties are quickly and effectively assessed and given the most appropriate treatment.

Instead of a traditional theory-heavy syllabus based on diagnosis, the new course takes a symptom-based approach. Crew members are trained to assess a patient and gather physiological markers to identify if someone is “big sick” or “little sick.” Simplified, “big sick” means the casualty has a time-critical, life-threatening illness or injury, while “little sick” means their injury or condition is not (immediately) life-threatening. This empowers crew members to make accurate and justifiable evacuation decisions, potentially summoning air assets (rescue helicopters) for the more serious “big sick” patients.

The crews are given waterproof casualty-care check-cards that use algorithms to help them assess, evaluate and treat a casualty effectively, without the need for significant retained theory knowledge. This helps reduce skill fade and improves patient treatment and outcome.

Savage won the Thomas Grey Silver Medal from The Marine Society for the course he developed. The course has been approved by the British Paramedic Association and the Royal College of Surgeons (Edinburgh).

International Development

Drowning accidents claim around 1.2 million lives worldwide each year – more than the number of people who die from malaria. In some countries, drowning is a leading cause of child death. Despite the scale of the problem, drowning is barely recognized.

RNLI lifeguards delivering training in Senegal. Photo by Mike Lavis.

The RNLI is increasing its international work to reduce this staggering loss of life. Most global drownings happen at the coast, in large bodies of water, or in floods – all environments in which the RNLI has expertise in drowning prevention.

Instead of setting up its own services overseas, the RNLI is helping others improve their own capabilities by delivering training, equipment and advice. By giving others the means to help themselves, the RNLI is trying to ensure developing countries can sustain their own lifesaving services.

Case Study: Lifeguard Training in Bangladesh

Bangladesh has one of the highest drowning rates in the world - drowning being the lead killer of children in the country - claiming around 18,000 lives a year. Hundreds of lives could be saved there every year now the country’s first lifesaving club has been set up with the help of the RNLI.

RNLI lifeguards delivering training in Bangladesh. Photo by Mike Lavis.

In March 2012, RNLI lifeguard trainers Darren Williams and Scott Davidson spent two weeks at Cox’s Bazar, one of Bangladesh’s busiest coastal locations, delivering a lifeguard training program to 15 Bangladeshi volunteers.

They adapted their usual course content and training aids, creating bespoke sessions to meet the needs of the Bangladeshi lifeguards and the environment in which they operate. They covered the essentials of lifeguard training, including: setting up a patrol, beach surveillance, recognizing when a person is in distress, using rescue equipment, and rescuing, assessing and treating casualties. They also delivered a “train the trainer” course, in which the volunteers could teach the skills they had learned to others. Within days of completing their training, the Bangladeshi lifeguards saved their first life.

RNLI Clinical Lead Paul Savage demonstrating casualty care. Photo by Nigel Millard.

Williams and Davidson returned to Bangladesh in October 2012. This time, working closely with the lifeguards they trained on their previous visit, they trained 60 more Bangladeshi lifeguards. They used a training manual developed by the RNLI specifically for use in low- and middle-income countries where specialist equipment and facilities are not available. They also helped the Bangladeshi lifeguards develop a coastal safety education program for schools and taught them how to deliver it. If the newly trained lifeguards can give vital advice in schools, providing children with an essential understanding of water safety, potentially hundreds of children’s lives can be saved each year.

Donating

The RNLI relies on voluntary donations for over 98 percent of its income. To find out more about its lifesaving work, or to make a donation, visit the RNLI website.

RNLI international development film

RNLI lifesaving training in Senegal film