Part 1 – Identifying common North American bears and their habitat

Part 2 - How to avoid encounters with bears

As medical providers, the old adage “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” is well understood and it is just as important to remember while in bear country. Avoiding an encounter with a bear seems an obvious way to prevent a dangerous encounter, but is often overlooked while people settle on firearms and/or repellants as a solution. In this article we will discuss how to decrease bear-human interactions both in populated areas and in the wilderness.

The best way to avoid an encounter is to decrease available food sources for the hungry bruins. This golden rule must be applied by municipalities, landowners, worksites, and wilderness users. Managing garbage and avoiding garbage conditioning bears is a key strategy at preventing habituation and eventual problems with either bear aggression or bear health. Communities, farms/ranches, worksites, and other sites in bear country should employ the use of bear proof garbage collection methods, and safely dispose of or incinerate waste.

Garbage management has been a cornerstone of bear management in the National Park System, with great success in places like Yellowstone National Park in Wyoming the U.S.A. and Banff National Park in Alberta, Canada. These programs drastically changed problem bear management almost immediately after implementation in the late 70’s. We know bear behavior enough to understand that the high caloric food found in garbage is a strong attractant to bears. The phrase, “A fed bear is a dead bear” is a good public education tool which highlights how attractive this food source can be. After discovering how efficient garbage is in gaining weight, many food-conditioned bears will be reluctant to leave. They will seek out other human food sources. Repetitive contact with humans my habituate bears to people, taking away their natural fear. Habituated bears may aggressively defend their food sources, or worse, see a person as a potential food source. When bears become habituated – and often “problematic” – they must be relocated (which comes with its own problems) or euthanized. Parks Canada takes the garbage issue so seriously that wardens may issue up to a $25,000 fine to anyone found feeding wildlife or not properly securing food or garbage within the national park.

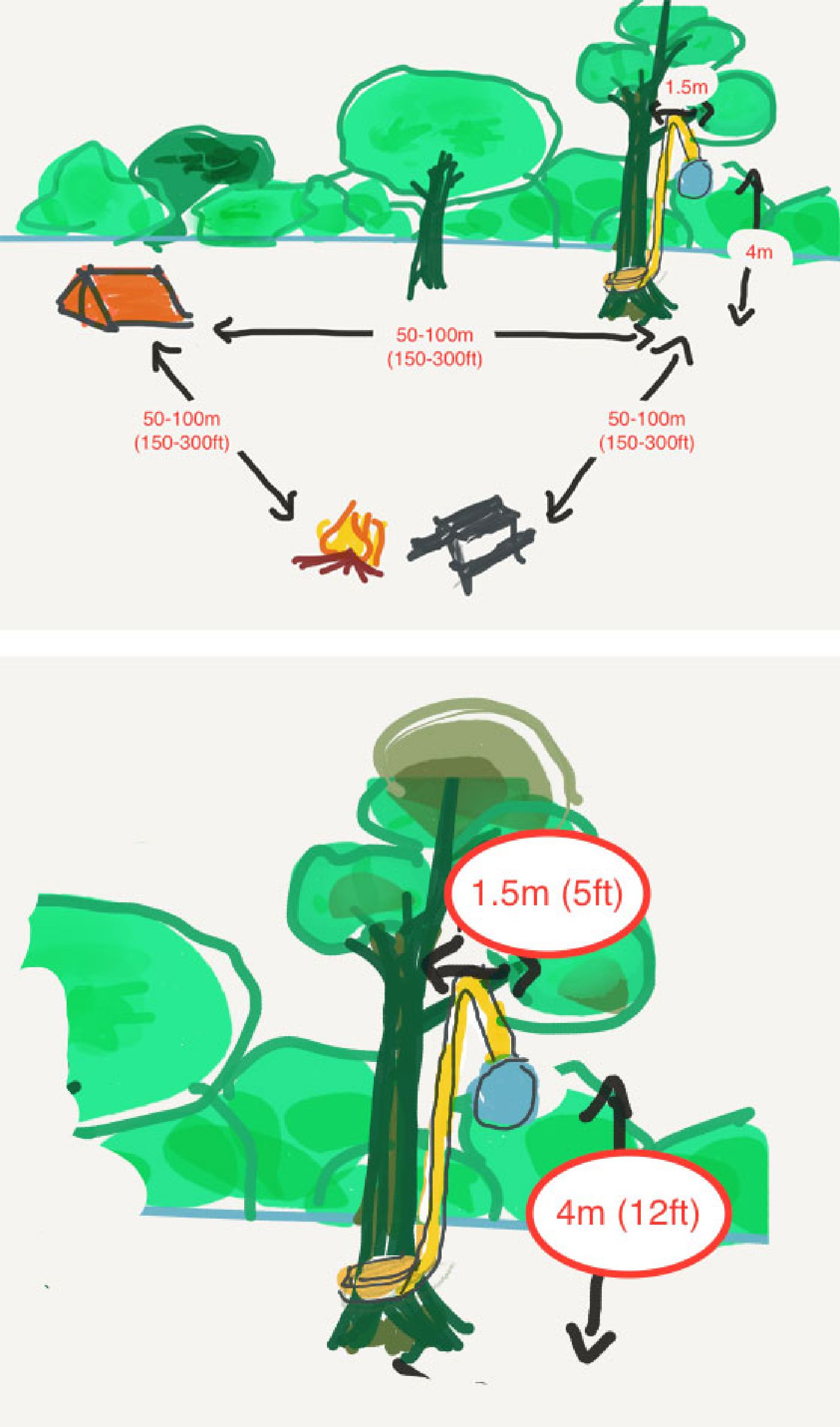

When working or recreating in bear country all sources of odor associated with human food must be considered. Camp layout is very important when you are settling for your stay. Ideally a camp layout should have different locations for storing and cooking food, both of which should both be at least 50-100m (150-300 ft.) away from sleeping areas. Remember this even if you are using a bear canister, as they are designed to stop the bear from accessing the food but they are still smelly. You do not wish for strong aromas from food to impregnate your sleeping area. Deodorant, cosmetics, soaps, and feminine hygiene products all contain strong scents and should always be kept away from sleeping areas. Ladies who are menstruating are not at an increased risk, but should properly care and dispose of hygiene products. Many backcountry campsites in national or state (provincial) parks have specially designed food lockers or hanging poles – ask at the local ranger office if such facilities are available. A number of camping areas on federal lands, including some National Parks in the U.S., require the use of approved bear canisters as hanging food is no longer legal. It is mandatory to properly use these canisters in Yosemite, Sequoia/King, Grande Teton, North Cascades, Olympic, Denali, Glacier Bay, Gates of the Arctic National Parks, Inyo National Forest, and sections of New York State Easter High Creek Park.

REI Bear Canister Basics

National Park Service Guide for Food Storage and Bear Cans

If you are not carrying a bear canister or you are unsure if the site you have chosen has designated storage facilities, make sure you pack in approximately 20m (60 ft.) of cord strong enough to lift and hang your smelly items, and learn one of the various methods for hanging your food at least 4m (12 ft.) off the ground. All cooking, cleaning, eating, or other activities that may produce odors should be done well away from your (or anyone else’s) sleeping area. Be mindful of the site and do not leave odors at a site that could potentially be someone else’s sleeping area in the future.

A great "How-to" page: https://www.princeton.edu/~oa/training/bearbag.shtml

Be especially wary if any signs of a carcass may be present. Carrion birds (ravens, vultures), rotten odor, or pieces of flesh are important signs. A bear will aggressively defend a kill and is an extremely common, and potentially deadly, cause of contact encounters. Bears may partially bury food sources, so relying strictly on seeing a dead animal is not reliable. Stumbling across one of these sites is extremely dangerous; hyper-vigilance, preparing for an attack, and immediately leaving the area the way you came is imperative.

Even if signs of activity are not present, areas with high-density food opportunities should be entered cautiously and only if going around is impossible. Often these areas have low visibility with many strong odors so you are more likely to surprise a bear and often at much closer range. Time of year will be an important factor of where bears may be eating and thus the areas to avoid. In spring, these areas include valley bottoms and sunny areas where new growth is occurring. During the summer many bears move higher into areas that bloom later, like the alpine or higher elevations. During the autumn the bears will again descend to spawning rivers or berry crops.

When traveling the likelihood of surprising a bear is much higher than when in camp, so additional precautions should be taken. Always be alert and aware of your surroundings. A person travelling in thick berry bushes beside a salmon-filled river obviously should take extra precautions. It is recommended that to decrease this possibility, backcountry users should talk and/or sing at regular intervals. Consider how far your voice will travel for the terrain you are in then speak or sing out accordingly. At times you could be calling out every 10-15 seconds. Using your voice is recommended, as it is a “human” noise. Bears naturally avoid humans, so identifying yourself as one is important. Bells, rattles, clapping, and other noises may not as effective at conveying this message (although some evidence has shown air horns to be effective if used regularly). Just because an area is well used by humans it does not mean that bears will not be present, so talk and sing even when there are other trail users. Be cautious to not startle a bear by randomly shouting loudly once you are in a berry patch or similar area. This may provoke an attack if you accidently snuck up behind the bruin before you yelled.

Remembering some simple practices can decrease the chance of an encounter with a bear when out in bear habitat. Decreasing the odors while in the backcountry and keeping your food and cooking areas well away from sleeping areas will help keep your campsite safer. Avoiding natural food sites and areas bears have been recently active, plus talking and singing often, will decrease the possibility of surprising a bruin and creating a negative encounter.

<iframe width="560" height="315" src="https://www.youtube.com/embed/UjvwNlAKfUs" title="YouTube video player" frameborder="0" allow="accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture" allowfullscreen></iframe>

For More Information:

Get Bear Smart Society

Parks Canada Bear Safety

Wildsmart Canada

Alberta Parks

References:

Gadd, Ben (2016) Handbook of the Canadian Rockies. Corax Press. Canmore, Canada

Hurrerro, Stephen (2003) Bear Attacks Their Causes and Avoidances. McClelland and Stewart Ltd. Toronto, Canada

Penteriani V., et al (2016) Human behaviour can trigger large carnivore attacks in developed countries. Scientific Reports. doi:10.1038/srep20552

Scheick, B.& McCown, B. (2014). Geographic distribution of American black bears in North America. Ursus: Vol. 25, Issue 1, pg(s) 24-33 doi: 10.2192/URSUS-D-12-00020.1

Wild Eye Productions, & AV Action Yukon Ltd.[Producers]. Staying Safe in Bear Country: a behavioral-based approach to reducing risk.[Motion Picture] Revised 2008.

Van Tighem, Kevin (2013) Bears Without Fear. Rocky Mountain Books. Canmore, Canada

Wilkerson, J., Moore, E., Zafren, K., ed. (2010) Medicine for Mountaineering & Other Wilderness Activities. 6th edition. The Mountaineers Books. Washington USA